What is truth? What is intelligence?

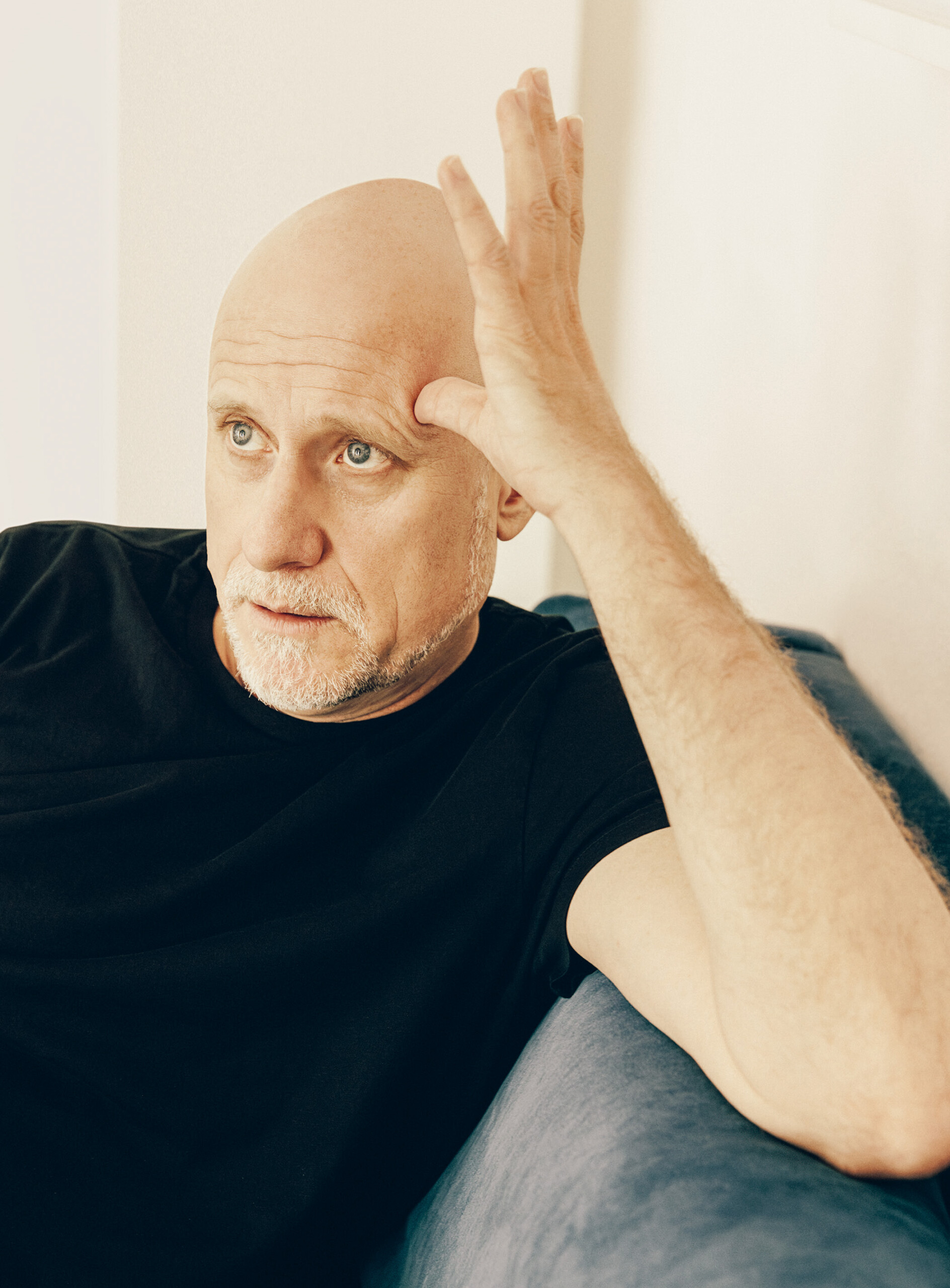

Trevor Paglen

What is truth? What is intelligence? It’s a warm day in early July in Trevor Paglen’s studio, a two-story carriage house in a quiet courtyard in Berlin’s Kreuzberg district. Sitting on a deep, squishy couch, I’m lobbing some of humanity’s shortest, most eternal questions to the artist. Through the windows of the airy upper space, trees wave in the breeze. On the shelving is a fantasy-game sculpture with a sword, an iridescent blue cube, fabric patches that look paramilitary, and skulls, some of whose crania are traced with phrenology subdivisions. On the walls hang richly pigmented, monochromatic canvases that Paglen says he can’t talk about just yet.

Artist, author, geographer, general polymath and ‘reverse cosmopolitan’ Trevor Paglen holds a Master of Fine Arts, as well as a PhD in geography from University of California Berkeley, and was a 2017 recipient of a MacArthur Foundation ‘genius’ grant. He is the author of seven books and is represented by Pace Gallery. His work has been widely exhibited in art institutions around the world. He lives in New York and Berlin, and spends some of his time in the American southwest tracking and photographing unknown objects orbiting the earth.

I think ‘intelligence’ is a dumb word, he says, before bursting into a peal of laughter. For him, intelligence is a stand-in for something that we vaguely feel but kind of can’t pin down …; it’s also connected to outdated, colonial notions of what a perfect human is meant to be, determined by hegemonic (that is, western) societies. But truth? That’s actually an interesting question. Truth is something that means a lot of different things in a lot of different contexts, he says, then pausing. If we narrow it down, we can talk about consensus reality, whatever that may be, and those have always been fictions in the sense that they’re social constructs. Because truth is malleable and consensus reality murky, it might be better to talk about philosophical mainstays like ethics or justice, but do we want to (or can we properly) go down those roads? We both backtrack. These are such big questions! I wish I had a PhD in philosophy, says Paglen, softly. I’m just an artist!

Paglen is far more than just an artist: the research and works that won him a coveted MacArthur Foundation grant in 2017 (a 625,000-dollar, no-strings-attached prize for scholars, artists and other notable people that in the U.S. is anecdotally known as the ‘genius grant’) are the result of a career that’s not only delved into humanity’s overarching questions but, even more so, shone a light on some of the concrete-yet-unseen workings of postmodernist life: the buildings from which military surveillance is conducted, the manual labour behind the datasets used to train Artificial Intelligence and the problems it can cause, and most recently, the psychological operations (‘psyops’) that governments (can) use to manipulate minds. The many threads running through Paglen’s art are in essence about, as he says, showing what invisibility looks like: the research and the artworks expose the many structures in our society that involve twisting not only information—truth, perhaps—but also identity and power, usually in ways we can’t perceive or even be fully aware of. And more recently, he’s turned the tables to show how much of what we see is based on us: When we perceive something, we’re very much bringing what we believe is true to our perception, he says. This is something that is weaponised, a lot.

Trevor Paglen’s artworks—ranging from sculpture and video to expansive digital projects and books—evolve from a relentless curiosity about the concealed structures, systems and surveillances that shape our world and places far beyond. Here, images and objects from his studio, preparations for an exhibition in Berlin and portraits of the artist.

Like our world, Paglen’s work contain layers of hidden references: the fabric patches are from his late-2000s Symbology series and are emblems of real-life classified military projects in the United States. The iridescent cube is made of irradiated glass from Fukushima, Japan, wrapped around a core of trinitite, a substance created when the first nuclear weapon melted desert sand in 1945. He’s shot two satellites into space as sculptures—the second, the temporary satellite Orbital Reflector, was a failed mission, its planned mirror-the-earth effect failing to materialise after its 3rd December 2018 launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, due to a governmental shutdown during the Trump administration (the capsule could not ‘deploy’ and reach its full dimensions without approval by governmental bodies like NASA).

There’s much more: the artist has photographed classified Central Intelligence Agency and National Security Association surveillance sites from great distances, resulting in hazy, poetic images (a technique called ‘limit telephotography’ combines cameras and telescopes to capture otherwise unreachable visual subjects), and his NSA-site film footage appears in journalist Laura Poitras’s Academy-Award-winning documentary film Citizenfour on surveillance whistleblower Edward Snowden. There are equally dreamy underwater images of the fibre-optic cables than run like arteries between the continents—making us realise the internet is the furthest thing from a cloud. For all the spacy locations and blurred aesthetics, the subjects of his images are often remarkably everyday. Of course the internet needs physical cables, just like telephone landlines do.

Then there’s Training Humans (2019-20), a collaborative project with Kate Crawford which explored and exposed the multitude of images used to train Artificial Intelligence systems since the 1960s: pictures the public was never meant to see. The project showed thousands of shots of real people from a database called ImageNet; a second component allowed web users to upload their own images and see what taxonomic labels might be used to categorise their own faces—all based on nouns entered into the system by underpaid workers from systems like Mechanical Turk. The results were troubling—a normal young man drinking beer might be categorised as an alcoholic, alky, boozer, lush, soaker, souse or an average woman labelled as slut—and went viral. The problem is that not all nouns are like ‘apple’, right? Some nouns are horrible, racist slurs, but it was so much worse than what you’d originally imagine, says Paglen. The tech world reacted quickly to the work, luckily, but only after the two revealed the immense power asymmetries—and reductiveness—inherent in machine learning.

Please select an offer and read the Complete Article Issue No 15 Subscriptions

Already Customer? Please login.