A question of SCALE

Sophie

DRIES

French architect and interior designer Sophie Dries, born in 1986, is among the most successful designers of her generation. A graduate of ENSA Paris-Malaquais and Aalto University in Helsinki, she also studied Contemporary Art at L’École du Louvre. After working with prestigious architecture and design offices such as Jean Nouvel, Pierre Yovanovitch and Christian Liaigre, Sophie Dries launched her studio in Paris in 2014 and opened a second location in Milan in 2017. Sophie Dries was selected for the 2022 AD100—Architectural Digest’s annual list of the world’s top 100 architecture and design firms—and was among Phaidon’s 100 World’s Best interior designers. She also won the Coup de Cœur at the 2022 AD & Land Rover Awards.

A cosmic essence of

MATTER

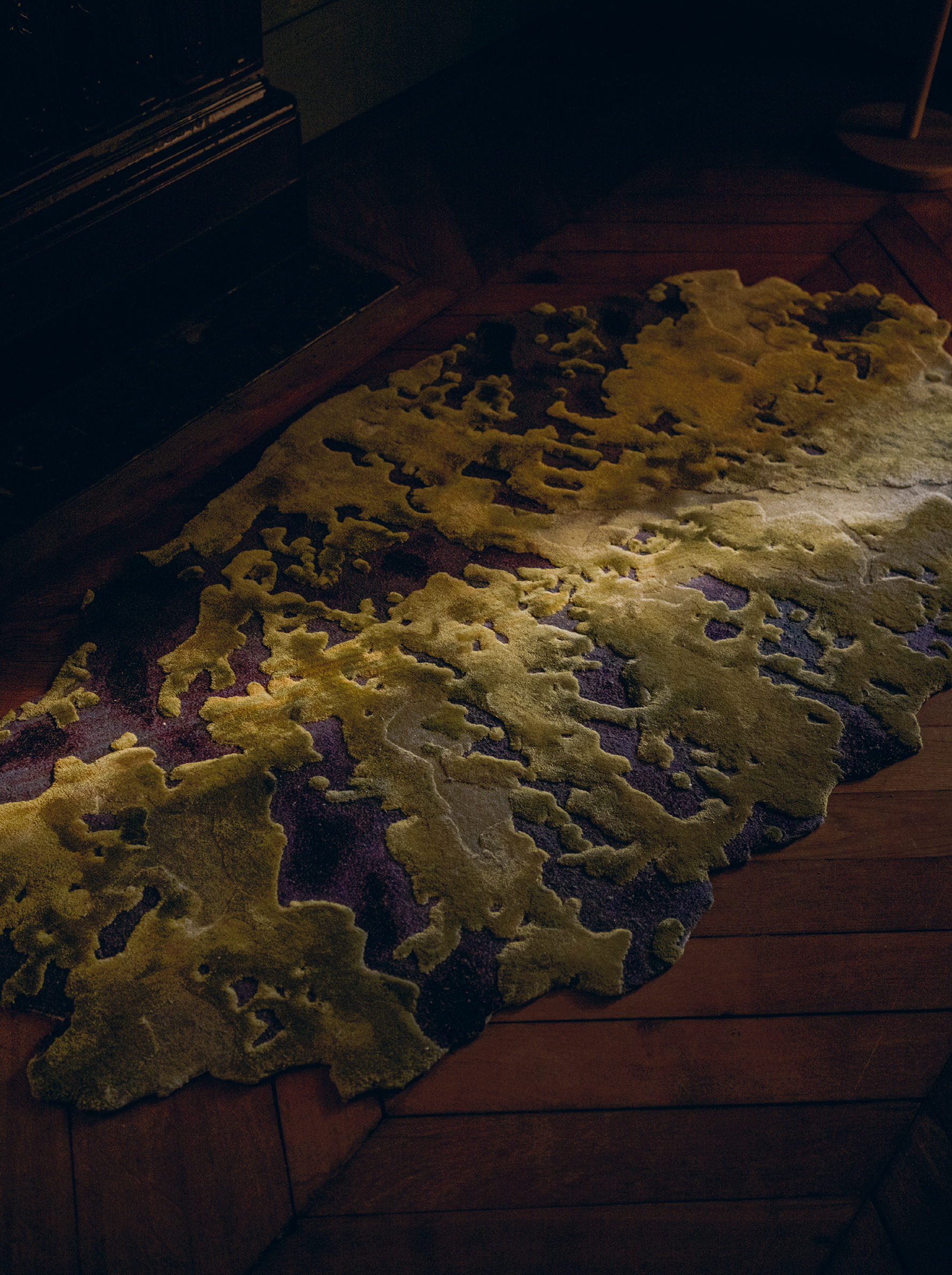

Far from being locked into a style, Dries draws inspiration from sources as disparate as the Age of Enlightenment and contemporary art. Arte Povera, with its use of elegantly natural materials and its quest for sustainability, is also a source of creative stimulation. The quintessence of material and craftsmanship is at the heart of her work: combining traditional artisanal techniques with new, contemporary know-how, whether it be in her interior architecture projects or for her furniture designs. Surrounded by exceptional craftspeople, she applies her knowledge of materials and constantly experiments with them, practising new ideas and methods to achieve the cosmic essence of matter, a concept held dear by Brâncuși. In a Zoom meeting, Dries talks with nomad magazine about the process of her work, the new importance of private living spaces and what it takes to make a place a home.

Individual environments are your speciality. What do you think is the most important part of a living space?

S

D

Designing someone’s home is almost like painting their portrait because it has to really showcase their personality. So, it's very important to get to know the person you work with and work for, and find out how they want to use this space. Some people regularly host guests, so their home is geared towards social representation. For them, the living and dining spaces are the most important parts. Others regard their home as a sanctuary, a place for themselves alone, an intimate space that is very different from their public image. There, the focus is more often on the bedroom or the study as secret spaces for collecting thoughts.

-

-

-

-

If the interior design is to reflect the intimacy of a family or an individual, how do you acquire this very personal information?

S

D

I never ask personal questions like Are you single? Intimacies have to be revealed through the dialogue we’re having around the apartment. I can learn a lot about a client’s personal situation by asking, say, how many bedrooms they want. The process of designing a space for someone usually takes a minimum of a year. Afterwards, you’re really familiar with the life of the people living there. So there’s no Q&A in the beginning, just a really long period of dialogue and setting everything up before starting to build.

-

-

-

-

It sounds like you take your time…

S

D

Absolutely! Generally, the design period for redoing a small apartment is about two months, but for bigger homes it can be four to five months. In these months before construction begins, we meet every week. That’s a lot of time to get to know your client. Designing a home for someone is not only like painting a portrait; it can sometimes also be a kind of therapy. People get divorced while their home is being redesigned! It didn’t happen to me, but it did to some of my colleagues. In any case, it’s very personal and even if you are super-rich, the most important budget is the one you’re putting into your home. So designing someone’s home is always a very critical and very delicate process.

-

-

-

-

What external factors are important in your design process?

S

D

Definitely the light. You really have to visit a space and understand what it’s like to live in it. A kitchen, for example, needs daylight. Another factor is what kind of possessions people want to bring in. I recently finished a three-floor-apartment in Rue Saint Honoré, Paris, for a couple who are art and design collectors, so it was very important to incorporate some of their major pieces in the new interior. They’ve lived there for 30 years, but now the kids have moved out and they wanted to use the space differently and make it more suitable for the years ahead, so we created a big new staircase and a lift. But when most people buy a new place, they want to get a new life along with it. They want to start over with everything and don’t take so much as a stick of their old furniture along.

-

-

-

-

How important are practical and functional issues? How do you make sure people can actually live and be comfortable in the spaces you create?

S

D

In the discussion phase, all these topics are reviewed over and over again. Also, I don’t want my clients to call me every day just because there’s a problem with something like scratches. So if someone likes a certain type of stone, I might explain that stone is fragile, and if the person wants something that’s bullet-proof I suggest another material. Most clients are okay with that. They don’t want something that just looks great; they want a place that’s comfortable. I have to create a balance between practical and aesthetic. It’s important not to lie to the clients and to educate them; to make them understand that some materials will age but that it’s a sign of beauty—a feature, not a flaw.

-

-

-

-

You work as an architect and interior designer, but you also design furniture and create artworks. You once said that you didn’t see why those fields had been separated in the first place. Can you elaborate on that?

S

D

I think it’s just a matter of scale. If I can design a house from scratch, I can design a table. Designing a chair is challenging, but you don’t need to be a furniture designer to do it. You can be an architect designing a chair; you can be a fashion designer designing a chair. I don’t believe in those boundaries. Just think of Alvar Aalto, Frank Lloyd Wright or Carlo Scarpa: alongside their great buildings, they all also designed every single object in them.

-

-

-

-

But aren’t the goals different?

S

D

Well, I never say, Oh, today I’m going to design a chair. It’s almost impossible for me to create something without any context or task. I have to do it for somebody or something. Otherwise, it would be just a pure exercise of form. A lot of my furniture and lighting designs are prototypes that came to mind during an interior design project, working with different artisans. So for me, it’s important to stay curious, to work and collaborate with different kinds of craftspeople, and not to do the same things over and over again.

-

-

-

-

In an article about you, the author was almost frustrated that your aesthetics are almost impossible to categorise—because you hate repeating yourself and you don’t copy others…

S

D

I don’t want to brand myself with a certain style. It’s not like: okay, you know me, I always do beige, or I always do curves, and it will fit just as well in New York as in Madrid… Of course it would be much easier, and I would have many more clients because everyone loves being able to recognise and buy things as brands. It’s true that maybe I don’t have a label that’s easy to sum up in three sentences, but I think what’s typical for my work is really my use of materials and textures with pure lines and to create contrast. I’m obsessed with paradoxes. I really want every project to be different and bespoke. So, my work remains an experiment, a new dialogue every time. Moreover, all my projects involve art. Most of my clients are collectors, and dialogue is easier with people who are open-minded about art.

-

-

-

-

To create a nice home, you either have to have talent and time, or the money to hire someone to do it for you. Is a beautiful living space rather an elitist thing?

S

D

Of course not everybody can have an interior designer, just like not everybody can have a personal tailor. However you do it, you have to be dedicated. The important thing is to create something that won’t turn out to be too ambitious if you don’t have everything you need to finish it. So I would recommend doing very pure things. I think Ikea and other affordable brands can offer great design. I’m not elitist about everything. In my work, I like to contrast typically bourgeois references with very raw materials, bring in some rust and broken edges. Jean Michel Frank, for example, was an interior architect to the bourgeoisie in the Roaring Twenties but definitely a rebel, mixing luxury and industrial materials, removing the mouldings in hôtels particuliers to replace them with clean and unadorned lines. So I ask myself: what would J. M. Frank do in 2022?

-

-

-

-

Do you have any other advice for designing a space?

S

D

Find the one central important point. If you have a window with a view, then I would place the seating there, maybe with a side table for a coffee cup. If you have a beautiful stucco ceiling, you should emphasise it. Or the fireplace. Concentrate the rest around this one central point. It has to be very simple, with a single focus. Always try to make it simpler and don’t put too much in one room. If you have a lot of bookshelves, place them symmetrically, because then you don’t notice them any more. They sort of disappear; that’s how our brain works. But if you want to emphasise something, break the symmetry.

-

-

-

-

You’ve said that you don’t like creating something just for the sake of it. Is there anything else that annoys you about contemporary architecture and design?

S

D

There are so many social media channels, magazines and blogs around that people are becoming more and more aware of interior design and interested in it. That’s great! What annoys me is the nostalgic approach to interior design, like the 1940s style. It’s just a style exercise mimicking an entire era. But some of my colleagues do that because that’s what people recognise, so something that they have already seen makes them feel safe. I mean, I love the Art Deco masters, I love Adolf Loos, Piero Portaluppi, Robert Mallet Stevens and the rest. But the challenge is to understand what to do in 2022, to do something new—and sometimes also to make mistakes. In some cases, I look at it later and say to myself: well, today I wouldn’t use this shape again. But at least I was experimenting! Sometimes my clients say: I want something like this. And I say: Well, that’s another designer, so if you want that, go and see that designer. I will never copy somebody, because I respect their creation and I don’t want people to copy me.

-

-

-

-

So your recipe is experimentation and surprise?

S

D

Yes, absolutely. If you create something that’s super-fashionable, it turns up on every blog and the day after, you can find it in Zara Home. If all you do is create the same thing for years, you go out of fashion. So it’s important not to fall back on an easy recipe and a blockbuster design, but to create something quite subtle that you need years to understand and interpret. Like Yves Saint Laurent said: fashion fades, but style is timeless.

-

-

-

-

You also love to play with shapes, as shown recently at the acclaimed Michel Vivien shoe store in Paris.

S

D

The wooden wave was an answer to a space that is super-long and narrow. We emphasised this flaw by creating a kind of canyon. Sometimes it’s the imperfection of a space that delivers an advantage. Andy Warhol said you should emphasise your faults and what makes you different from the norm. But the wave is not only aesthetic: it’s hiding a lot of technical features, like the air-conditioning, heating system and storage. If I had been working in a different location, I wouldn’t have created the same design. So, for me, interior design is really like haute couture; it really depends on the space and how to best emphasise the feature you have there.

-

-

-

-

The flower shop you designed for Arturo Arita in Paris invites the customer into a neo-romantic nineteenth-century grotto. Where did you get your inspiration?

S

D

In Italy, where I still live some of the time, and in Germany. I absolutely love the Bavarian castles of Ludwig II! I went there just to visit them all. Ludwig was crazy about grottoes. As I’ve said before, it’s very important to me to be in my era, in my epoch of 2022, but it’s also very important to know your classics and to always delve into past centuries.

-

-

-

-

You like to use the term deus loci or genius loci, meaning the spirit of the place. What exactly does that mean to you?

S

D

That’s what I meant when I said I don’t have a preconceived recipe. I go into a space and I try to fill it. Maybe there’s something mystical about it; maybe I’m the witch of design! I experience a space, and then I design in accordance with what I feel. But it’s not only mystical. The plan and the technical aspects have to work as well.

-

-

-

-

How did you furnish your own home in Paris?

S

D

Before we moved there, we lived in Italy for almost three years, and before that I lived in a Paris loft that I totally redesigned and furnished; every piece was made for that space only. So we didn’t have much furniture in the beginning, and my partner and I were living in an almost empty apartment. All we had was a mattress and two Gaetano Pesce chairs as side tables. We tried sleeping in different rooms—and we found some rooms are absolutely not meant for sleeping in! I’m not talking about feng shui here because I don’t know so much about it, but some rooms are definitely created to be daytime rooms. You have to experiment. It took two years to finish the design of the apartment. Because it’s a classic Haussmann apartment, we wanted to create a contrast between contemporary pieces and the bourgeois backdrop. I ordered some pieces from designers that I know and we collected some vintage furniture from our own era,—the Eighties and the Nineties—by Philippe Starck, Gaetano Pesce, Ettore Sottsass. People’s nostalgia mostly focuses on the period they were born. For me, it didn’t make sense to use vintage pieces from the Fifties by Charlotte Perriand, Jeanneret or Le Corbusier, say, because those interior designers were relevant to a different generation.

-

-

-

-

How important is the aspect of sustainability for you?

S

D

First of all, we all have to develop an awareness of our planet Earth, of production and waste. As a designer, I think we need to create objects we want to keep forever, for the whole of our lifetime, and also maybe hand down to our children. I don’t want to make objects that people will sell or throw away in three years. Maybe my items are more expensive, but they’re handmade. If you want to purchase them, you’ll need to wait—first to be able to afford them, and then for me to produce them. Most of them are only produced on request. This process is important to me. In terms of ethics and aesthetics, I only use natural materials because they will age nicely, unlike artificial materials. If you don’t have the budget for marble, we won’t put in fake marble; we’ll use metal or concrete, and it will age beautifully. I don’t think it’s a problem if a table has a few scratches; a scratch is interesting on wood and on natural materials. But if you’ve used resin, that scratch diminishes the value of the piece.

-

-

-

-

But with natural materials, you have the problem of sourcing…

S

D

Sure. I would never use exotic wood just because I wanted to have its particular colour. Together with artisans and craftspeople, we are trying to find a smart and sustainable way to make beautiful objects. And we use what we have. Now, with COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine, we are having to rethink some of the materials we are using.

-

-

-

-

What are you thinking about specifically?

S

D

At the moment, we have a lot of issues with shortages of metal and wood, and with rising prices. A lot of wood came from Ukraine. So we have to find some more local materials that can be sourced from not too far away.

-

-

-

-

Can we talk a little about your childhood and youth? Was there any indication that you would become an architect or develop an interest in architecture or design?

S

D

No, not really. My parents aren’t architects. But I was always into making things with my hands. I actually wanted to become a chemist when I was a child. I had a children’s chemistry set and enjoyed mixing materials to make them explode, burn or turn into something else. In a way, this is exactly what I’m doing now with the artisans I work with, when I go to their workshops and we try to experiment with new materials and textures.

-

-

-

-

You’ve studied in France and Finland, you have an office in Milan, and you’re working on projects all over the world. Is there some kind of national taste, or is taste universal when it comes to interior design?

S

D

It truly depends on where you are. Scandinavian countries definitely have a major focus on interiors because their winters are so long. That’s why they are super good at furniture design, especially with pinewood because they have so much of it and are very craft-oriented people. It’s totally different from the Mediterranean countries, where the outdoors and the light are very important in the house. There you have the aspect of the climate, which definitely changes things. The historical context of the city and of the building where your project is located is also very important.

-

-

-

-

Is that a challenge for you? Do you like that?

S

D

Yes, it’s totally a challenge, and a major passion of mine as well. When I designed for the German-Austrian brand, Kaia, I visited a lot of the local traditional glassblowers. It’s important for me to research the things that are typical of every region and to discover some local crafts. It’s like a treasure hunt, and I can be an explorer.

-

-

-

-

Compared to when you began in 2014, do you see any changes in what people want from their homes now?

S

D

Firstly, people have become so much more interested in interior design culture through social media, magazines or blogs. And the pandemic has definitely changed a lot of our living habits, because your home is now also your working space. A lot of people have kept up the habit of working from home, at least for a few days a week. Bringing a workspace into an existing apartment is a really new idea. Kitchens have also become more and more important. The pandemic has definitely created a huge surge in private demand. During the last few years, I’ve had more private residential projects than B2B because people have been travelling less and want to have their homes upgraded. I’ve also had a lot of requests about furniture. By travelling less, people have saved money and wanted to improve their homes, so they were buying more furniture. I would also say people have become more conscious of where and how their pieces are made. They want to understand, and maybe even tell their guests, because renovating your house creates a lot of anecdotes you can tell your family and friends.

-

-

-

-

In your home, where do you spend most of your time?

S

D

I have a big dining-room, which is where I am right now, and it’s where I work when I’m not in my office. When I’m not working, I am in the living-room by the fire, far from any technology. It’s really interesting how, 50 years ago, we used to think the future was full of technology. Now technology really is everywhere, but we don’t want to see it; we want the technology not to be visible. This is quite challenging for us as interior designers: we have to hide all the technical stuff in your homes and make it feel as if you were in a country retreat—but with all the technology.

-

-

-

-

-

Thank you very much for your time, Sophie.