Khartoum Syndrome

While searching for Jonas, a refugee from Eritrea, in Sudan,

photographer Matthias Ziegler and author Michael Obert came across

the quagmire of international human trafficking.

Theirs was an apparently hopeless task. Notes on the most lethal escape route in the world.

nomad takes a look at their travel notes and in doing so gains

an insight into the fate of individuals on the run–or how far people will

go for the chance of a liveable future.

He fits the description. His name is Jonas, he is a 20 year old Eritrean fleeing from the horn of Africa en route for Germany. His right upper arm is covered in scars and his neck bears the mark of cuts, perhaps made by a wire. He sits down nervously at our table. His breathing is fast, his hands tremble. We assure him that he has nothing to fear from us, that we are searching for Jonas, whom we have never met, but who is the brother of a friend in Frankfurt.

Flies are crawling all over the little plastic tables of the café. We can hear the click-clack of the beads of the wooden curtain as it sways in the doorway. Outside, in the heat haze, we can see the boxy brick living quarters, where the Saharan desert sand has drifted up creating dunes against the sides. Young men with haggard faces hurry by, a little stooped, glancing about nervously, on an epic journey that will take them across a network of roads, tracks, cattle and smugglers’ paths for more than 5,000 kilometres across the deserts of Libya, Egypt and finally, to the shores of the Mediterranean. This is the most lethal escape route in the world—and the gateway to Europe.

There are as many starting points as there are reasons to embark on a journey which will take them many months, sometimes even years. However, sooner or later, all roads lead to the city of a million inhabitants at the confluence of the Blue and the White Nile, in which we have been searching in vain for days for Jonas, the young Eritrean. Khartoum—capital of the Republic of Sudan—is a gigantic transit station for refugees from all parts of the African continent and a magnet for traffickers in human beings.

Nobody knows exactly how many people sheltering in this mud and concrete jungle are waiting for the opportunity to embark on what is known as the Khartoum route through the Sahara to reach the shores of the Mediterranean sea, where many thousands have drowned in recent years. They are escaping from war, state brutality and extreme poverty. They come from Somalia, South Sudan and Ethiopia, from Chad, the Central African Republic, the Congo and Burundi, even from West African countries like Nigeria, Mali and Mauretania.

Alone from neighbouring Eritrea, hundreds of thousands have come here. Our search for Jonas seems hopeless. We only have his first name, his place of birth and a photo taken twenty years ago when he was a toddler. We have known Jonas’s family for years. “Give my brother this picture”, asked his brother, himself a refugee, in Frankfurt when he heard we were travelling to Khartoum. His voice was imploring, as if he was placing Jonas’s fate in our hands along with the photo. Yet when we arrive in Khartoum, the telephone number we have for Jonas is unobtainable. Time and again, we try to phone, but the line is dead. All our efforts prove fruitless.

In the café, the young Eritrean we are hoping might be Jonas, is fingering the cuts on his neck. “They came out of nowhere…eight men with swords and kalashnikovs”, he suddenly blurts out, adding: “They set about us like animals”. He asks us for a handkerchief. One of the wounds has opened and blood is dripping onto the table. The Khartoum route is controlled by one of the most horrifying networks of international human traffickers. According to the United Nations, around 30,000 refugees have been kidnapped and brutally tortured since 2009, for the purposes of extracting ransom money from the families.

Refugee routes

to Europe via Khartoum

portrait one

16 years old

Fleeing from unlimited compulsory military

service in Eritrea for the past two months and more

Would like to be a pilot or an astronaut

This is Jonas, a young 16 year old Eritrean, his hair slicked down with gel and drawn back into a small plait. He has been in Khartoum for two months. His father has also escaped, but is stuck in Israel. His aunt perished in the Sahara. One brother is waiting in Libya for a ship to take him across the Mediterranean. Two uncles are in refugee camps in Ethiopia. There are brothers and cousins in Europe and Dubai.

A family torn apart. Escape has scattered the family across the continents. A global crisis and a global phenomenon. Jonas is hoping to reach relatives in Dortmund. Alone, and at 16 years of age? Crossing the Sahara and war-torn Libya? Is he afraid of human traffickers? “The Almighty will help me.” And what of the Mediterranean sea? “I can swim.”

portrait two

20 years old

Fleeing from political persecution

in Eritrea for the past two and an half years

Occupation baker

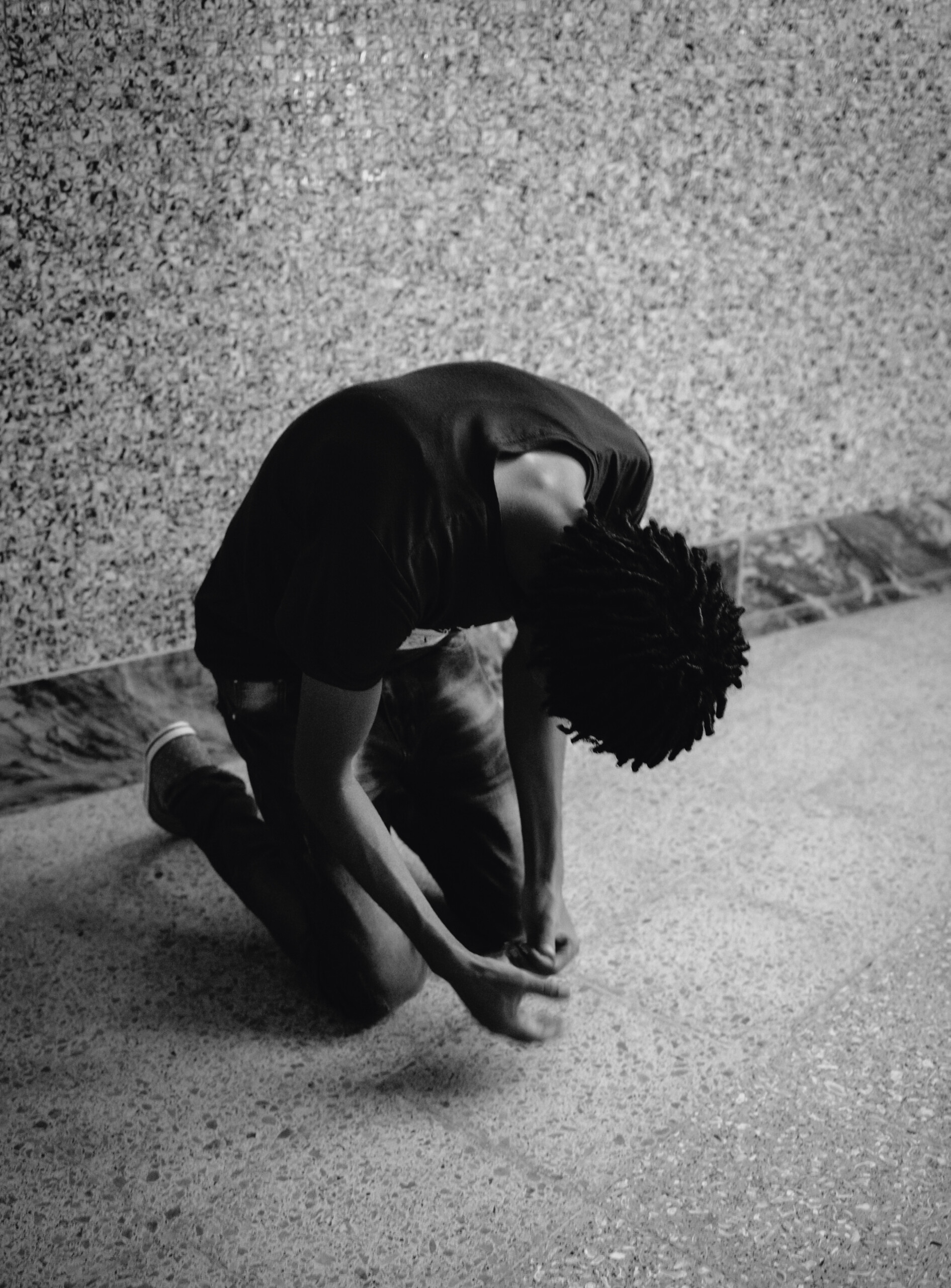

For many days, he and another nine companions were fleeing the military dictatorship ruling neighbouring Eritrea on foot. At the desert border with Sudan, heavily armed men attacked them and forced them into their offroad vehicles at gunpoint with kalashnikovs and took them to their hideout in the wilderness. Jonas recalled: “There was a single tree, some tents and some camels”, pressing our handkerchief to his neck with one hand and holding the toddler photo in the other “…and there were more hostages, more than eighty Eritreans.”

Chained to heavy metal rings, the human traffickers let Jonas kneel and roast in the heat. He was given one beaker of water a day, half a slice of bread in the mornings and he was beaten with a power cable every evening. “They were demanding 15,000 dollars for each of us”, Jonas told us. The picture in his hand seems forgotten now as he goes on: “They shouted at us to ring our families and tell them to pay up!” When Jonas refused, they put out lighted cigarettes on his arms, wrapped a wire around his neck and throttled him, then they laid plastic bags on his shoulders and lit them. In the café, Jonas pulls his shirt down to show us. His shoulder blade is deeply scarred down to the bone. “At first, they did it for the money, but then, they did it just for fun.”

He remembers the photo. Almost tenderly, he touches the faces of the two boys, dressed in pastel colour sitting demurely on a blanket on the grass.The older boy holds a yellow balloon, while the younger one laughs and screws up his eyes. Jonas whispers: “Brother”, then shakes his head. He is not the boy we are seeking.

portrait three

22 years old

Fleeing from compulsory recruitment

in Eritrea for the past five years

Occupation Nurse

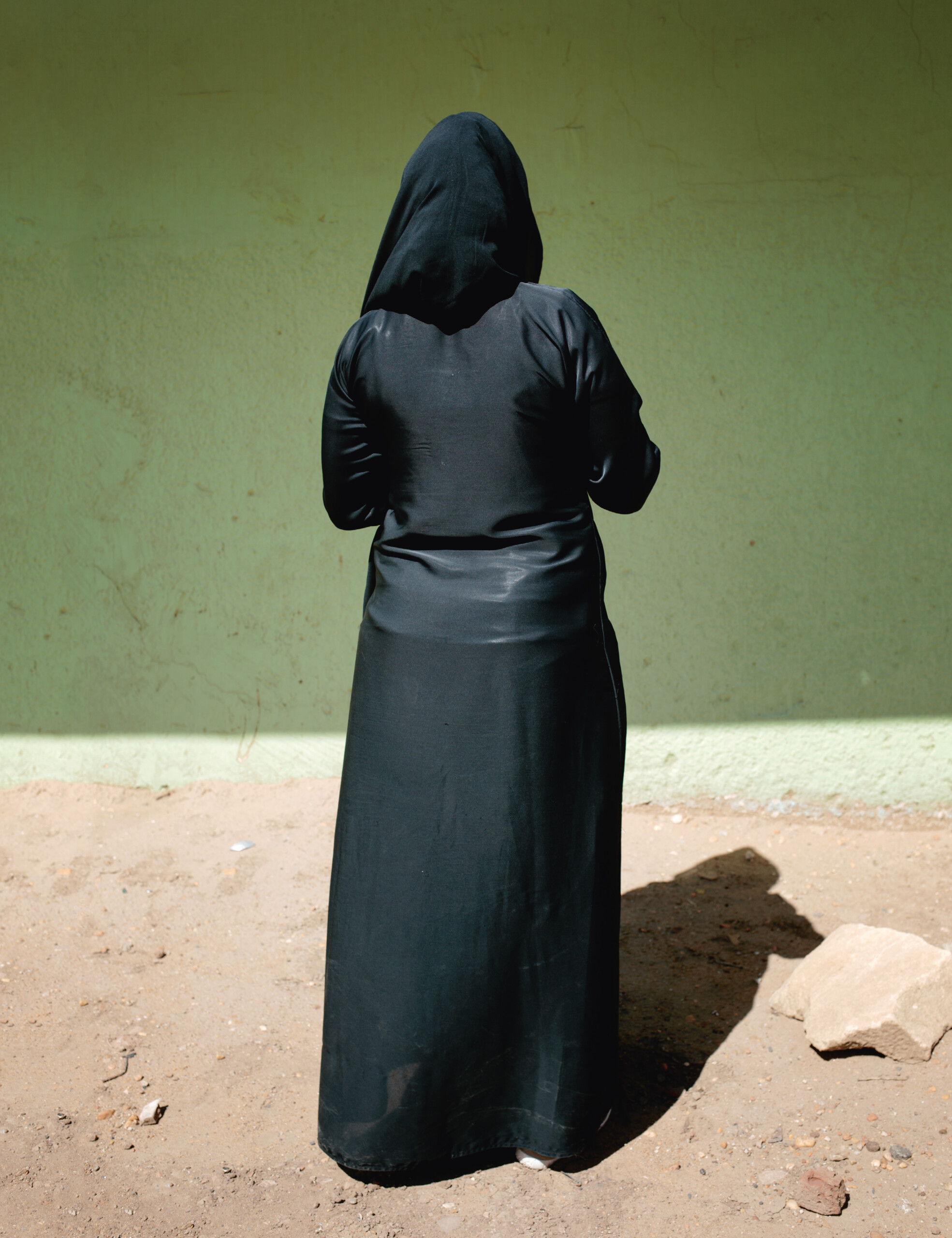

Merhawit doesn’t want to be seen with us. She is afraid that secret agents could be following our tracks. After days of negotiating back and forth, we finally meet in a car. As we drive, the airstream makes the fabric curtains on the windows flutter, while Merhawit describes a shack made of branches and goat leather, which is “hardly bigger than a coffin”. This is where the human traffickers bound the young Eritrean to a stake on the ground.

Merhawit continues: “They stood in a line in the desert”. Her hair is plaited under a headscarf and she has painted tiny pink spots on her fingernails. In the first days, she counted her rapists. “I really thought that when the number had reached 50,000 it would be over.” That thought gave her some inner strength. But as the weeks went by, more and more came and at some point, Merhawit stopped counting. She says she is only telling us her story in the hope that something will change if Europe hears of the gruesome horrors happening on the Khartoum route.

After 13 months being held captive by the rapists, her family finally managed to find the 35,000 dollar ransom money. “But intead of letting me go”, Merhawit tells us in the car, “…they sold me on to the next bunch.” And so the abuse continued until her torturers left her, half dead, in the desert to die. It is a miracle that she survived. A camel train of nomads found her and took her to a Red Crescent tented camp.

Merhawit has suffered torture which is beyond imagination. Yet she does not appear to us as a victim. She sits upright in the car. She does not shrink from looking us in the eye. She does not complain, she does not weep, she is determined to take back control of her life. Like all the refugees we meet en route, Merhawit has concrete plans as to her future. In an unwavering voice, she tells us: “I will work as a nurse in Frankfurt. I will look after and care for human beings, regardless of the colour of their skin.”

portrait four

22 years old

Fleeing from political persecution

in Ereitrea for the past four years

Occupation carpenter

In a snooker hall in El Grief, a poor district in east Khartoum, where tens of thousands Eritrean refugees live, young men pore over our photo. Although Jonas was still a baby when the photo was taken, they study his eyes, nose and mouth. “He’s Eritrean: he’s one of us!” All we know is that Jonas comes from Dekemhare, a small town in south western Eritrea. Suddenly, there is excitement among the men. They call for a Jonas. From Dekemhare. He is missing two fingers. He studies the photo with care. Finally, he says: “But I’m sure your Jonas is still alive.”

Then he proceeds to tell us his story. “In Eritrea, the government dictates how you live and what to think.” The Orwellian police state he describes compels relatives and neighbours to spy on each other and presses young men and women into military service for an unlimited period of time. Whilst taking part in a critical school play, the young Jonas, who was 17 years old at the time, was arrested on stage, tortured in a secret prison and only released months later.

In 2012 he escaped on foot to eastern Sudan, but there, human traffickers abducted him from a UN refugee camp. Once again, Jonas went through the hell of torture. It lasted 18 months. “Not till I was on the verge of death did I ring my family.” The ransom for him was 40,000 dollars. His parents, poor Eritrean farmers, sold their home, their land and their cattle and the rest of the money was supplied by relatives abroad in Germany, Sweden and Switzerland. Jonas hopes to go to Stuttgart, because that’s where he has some Eritrean friends and “because Stuttgart urgently needs carpenters.”

portrait five

20 years old

Fleeing from unlimited compulsory military

service in Eritrea for the past eighteen months

He hopes to be a car mechanic

The day before our departure, we are at a junction in the east of Khartoum. In the meanwhile, we have managed to spek to Jonas on the telephone. We had feared the worst: but all that had happened was that he had run out of money for the SIM card, which is why the line was dead. Then, finally, after 13 days and 18 hours spent in Eritrean restaurants, cafés and snooker halls meeting dozens of similarly-named young men and hearing their stories—Jonas alights from the bus. Our Jonas. We recognise him instantly. He is the spitting image of his brother, our friend in Frankfurt: round cheeks, little moustache on his upper lip, a shy look: he is a shy young man, wobbling nervously on his legs as he shakes our hand.

Later, he tells us in the tiny room he shares with three other Eritreans: “My life is slipping through my fingers like sand.” His brother’s greatest fear is that Jonas has fallen into the hands of people smugglers taking him to the shores of the Mediterranean. The family in Frankfurt are looking for a legal way of bringing Jonas into German, perhaps on a study visa, or some other German refugee intake programme.

However, with every passing day spent waiting in Khartoum without any work, under constant threat from the secret police and the henchmen of the human traffickers, Jonas’ fear of the lethal escape route is diminishing.

We give him the baby photo. The edges are ragged and the corners bent from the many hands it has been through. Jonas stares at the picture for ages. He is unable to speak. We all have tears in our eyes. On the reverse side of the photo are the words: “Be patient. We will find a way.”