What if we had another month between June and July?

Kalyani Tupkary

The designer Kalyani Tupkary would not shies away from calling herself an expert of time and timekeeping. She rather sees herself as a “gentle generalist” who likes “cross-pollinating ideas across disciplines” and “inhabiting the in-between spaces”. Indeed, she is not easily pigeonholed. Her practice is situated between craft, design and technology, and between product and speculative design. However, through her investigation of the calendar, she has become an expert of sorts on the notion of time and practices of timekeeping. Her alternative calendar designs invite us to explore temporalities other than our own. Talking to her about time offers rare insights into our assumptions about work and leisure, travel and vacation.

We talk across several time zones. Kalyani has just moved to a new place south of San Francisco. Her work for Twitch as a product design lead has brought her here from New York, where she mastered at Parsons School of Design following her degree in industrial design from the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, India. We arranged to meet by reference to the Gregorian calendar and standard time—Kalyani is on Pacific Standard Time, I am on Central European Time. If we had used one of her calendars, our planning might have been more difficult, if not impossible.

Here a year has only weeks. Each week with 10 days. Every day lasts for 10 hours, with 100 minutes in an hour and 100 seconds in a minute.

“Oh my god!! I just heard—was she really born at ten past hundred? And on the tenth, as well? What a lucky baby. Congratulations! Can’t wait to meet the little one.”

When we travel, we inhabit time differently. My 16-year-old son, who is on a historic sailing boat bound homewards, still has two months of his travels ahead. On their way across the Atlantic to their destination in the Caribbean, they were resetting the clock with every longitude passed as they travelled westwards. On their return, they will do the reverse. This slow mode of travel allows the organism to adjust—as opposed to travelling by plane, which disjoints us from time and propels our bodies into jetlag. Also, life on board a sailing vessel is not divided into night and day but into six four-hour watches, with four hours of duty followed by four hours of rest. On historic trade ships, each cabin bed could thus be occupied by two crew members alternately.

Just as shifts are tools to align time and labour more efficiently, clocks and calendars are tools designed to measure and standardize time. As we schedule a weekend trip or our annual summer holidays, we rely on our calendar with its familiar rhythm of work days and weekends. Like everyone else, we try to optimize our travel plans around national, religious and bank holidays. The tourism industry proposes special deals to those who travel in low season or at off-peak hours. All the while, we rarely give a thought to the fact that the calendar itself is a construct, partly based on scientific principles, partly on social conventions. What if we lived by a different calendar? For instance, one which divides the year into 13 months of 28 days each, with an extra month between June and July and a ‘leftover’ day at the end of each year? Would the new month become the main holiday season and relegate August to a ‘back-to-school’ month? What if our calendar was organized according to the moon, and the night was variable depending on the phases of the moon? Would hotel rates be calculated according to the night’s length, with a No Moon night charged at less than a Waxing Crescent or a Full Moon? What if our calendar was divided between even and odd days, and people born on an even day would always work on even and rest on odd days, and vice versa? How would mixed couples find ways to spend their free time together? Would parents need to have two babysitters to cover their work days?

These are just some of the questions which emerge when we look at the calendars proposed by Kalyani Tupkary as part of her CALENDAR COLLECTIVE, and when we listen to the fictional voicemails which she recorded to provide a sense of what it would be like to inhabit a world which adheres to this or that calendar. Her calendars can be seen as an attempt to restore different notions of time. Our calendar and clocks promote “the normative understanding of time as linear, objective and neutral”, says Kalyani. “But our lived experience of time is divergent.” She points out how our sense of the passage of time is subjective and malleable, depending on context and activity, and how the value attributed to our time depends on factors that are unevenly distributed, such as our line of work, our social and economic status, even the phase of life we are in. Rather than being neutral, time is entrenched in political, economic and administrative interests. Kalyani gained these insights through her research and the participatory workshops that she conducted with people from different cultural backgrounds, age groups and walks of life, and they later came to inform her series of alternate calendars.

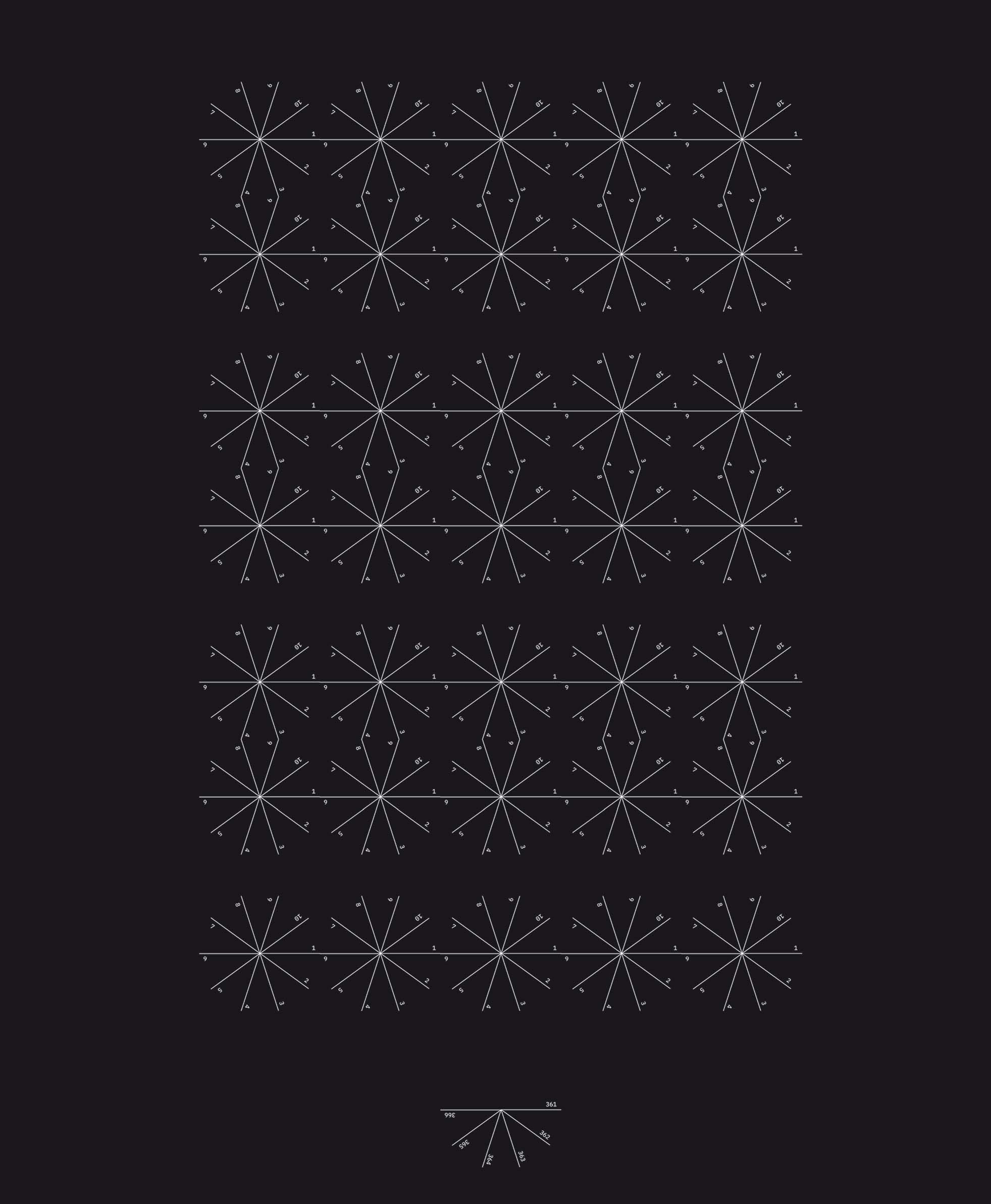

Her CALENDAR COLLECTIVE—which so far includes nine calendars, each with its own visualization, and one printed version—makes use of the “calendar as a subversive tool to challenge the dominant time structures and rebuild diverse structures”. Each of them is a visual exploration of one guiding theme, be it the sun, the moon, the metric system or the fact that calendar days can be divided between even and odd days: “When we think of a calendar, we associate certain aesthetics and materialities with it”, Kalyani says. While some of her calendars align to familiar representations, others radically depart from them. While some are more likely to function, others enter the realm of the unreal. The SUN calendar, for instance, features the typical grid, but provides no information about the weekdays. The COLOUR calendar features pastel-coloured field paintings with delicate gradients which are specific for each day and location. Here, “some hours are more colourful than others”, as may be seen in the examples of New York and Mumbai, each with distinctly different pastel hues. A similarly speculative version is the FLOWER BLOSSOMING calendar: “Here, time blooms and withers with the opening and closing of flowers.” In both versions, time is more intimately aligned to the affordances of nature and daylight and measured in shades and gradients rather than in hours and minutes. For the FIXED calendar, Kalyani broke free from the grid structure and opted for a concentric design which recalls a round cake rack or a spider’s web, with each of the 13 months occupying one slice extending outwards from the centre outwards, and with days 1 to 28 sitting on the concentric circles.

But how did it all start? Her interest in alternate temporalities was sparked when she moved from her native India to the USA for her Master’s degree at Parsons: “When you are away from home, you are temporarily disoriented. The rhythms of India, where my family lives, the festivals, the holidays, are different than in the US. As I started working with time for my thesis, I had this lived experience of how you occupy time differently in India than here in the West, but no way to explore it in a legible way.” When her father mentioned the Indian National Calendar to her, also known as the Saka calendar, “calendars emerged as this tool”. She had not been aware of that calendar, even though it has coexisted with the Gregorian model since 1952: “Before, there were 30 different calendars. They were intricate, complex and subject to local variations, even in their method of time reckoning. With independence from colonial rule, it was desired that there should be a collective identity by drawing temporal borders via a joint calendar for our civic, social and other purposes.” The government appointed the National Calendar Reform Committee, with astrophysicists, astronomists and mathematicians among its members, to define a calendar for the newly independent Indian state. This aroused Kalyani’s curiosity: “As I was digging deeper, I came across further examples from other countries and cultures. All these alternate calendars have existed, and yet now we can’t possibly think beyond the Gregorian calendar.”

Please select an offer and read the Complete Article Issue No 16 Subscriptions

Already Customer? Please login.