The power of Oil

John Gerrard

On the driving force of modernity.

John Gerrard

John Gerrard grew up in Ireland.His mother was an environmental activist. While still a student, he began to explore the potential offered by digital simulation.

He attended the School of the Art Institute in Chicago and Trinity College in Dublin. He focuses on game-engine potentialities in his art and for the past decade he has worked with a programming team in Vienna, Austria, to create extraordinarily detailed simulation-sculptures. Gerrard lives and works in Vienna and Dublin.

Gerrards work delves into the powers and influences that drive our world—both visible and concealed. Using sophisticated digital stimulation technology normally used for gaming, his pieces expose and comment on nodes and structures of power, trace, time- and energy-based processes, and are often in view in public space as well in museums.

Interview

John Gerrard is concerned. He’s concerned about the power that originally drove modernity. He’s concerned about the material that drives us today—oil—and what alternatives might exist. The 43-year-old artist grew up in Ireland, the son of an environmental activist, and became intrigued with digital techniques and potentialities during art school. A later stint as an artist-in-residence at Ars Electronica in Linz forged ties to Austria. For the past decade, Gerrard has been creating art within the game engine with a Vienna-based programming team. The resulting works are eerily detailed simulated realities that comment upon, expose and critique today’s underlying power structures, and are often on view in public space.

In a sleek storefront studio overlooking a park in Vienna’s sixth district, nomad spoke to Gerrard about his evocative artworks the power of petroleum, and how our very reality is distorted by the fuel we use—but what alternatives might be in store.

Kimberly Bradley

Oh, this is lovely (indicating the cheese, hearty bread, and fruits Gerrard has set out on his studio table).

John Gerrard

This Bergkäse (mountain cheese) is the best in Austria.

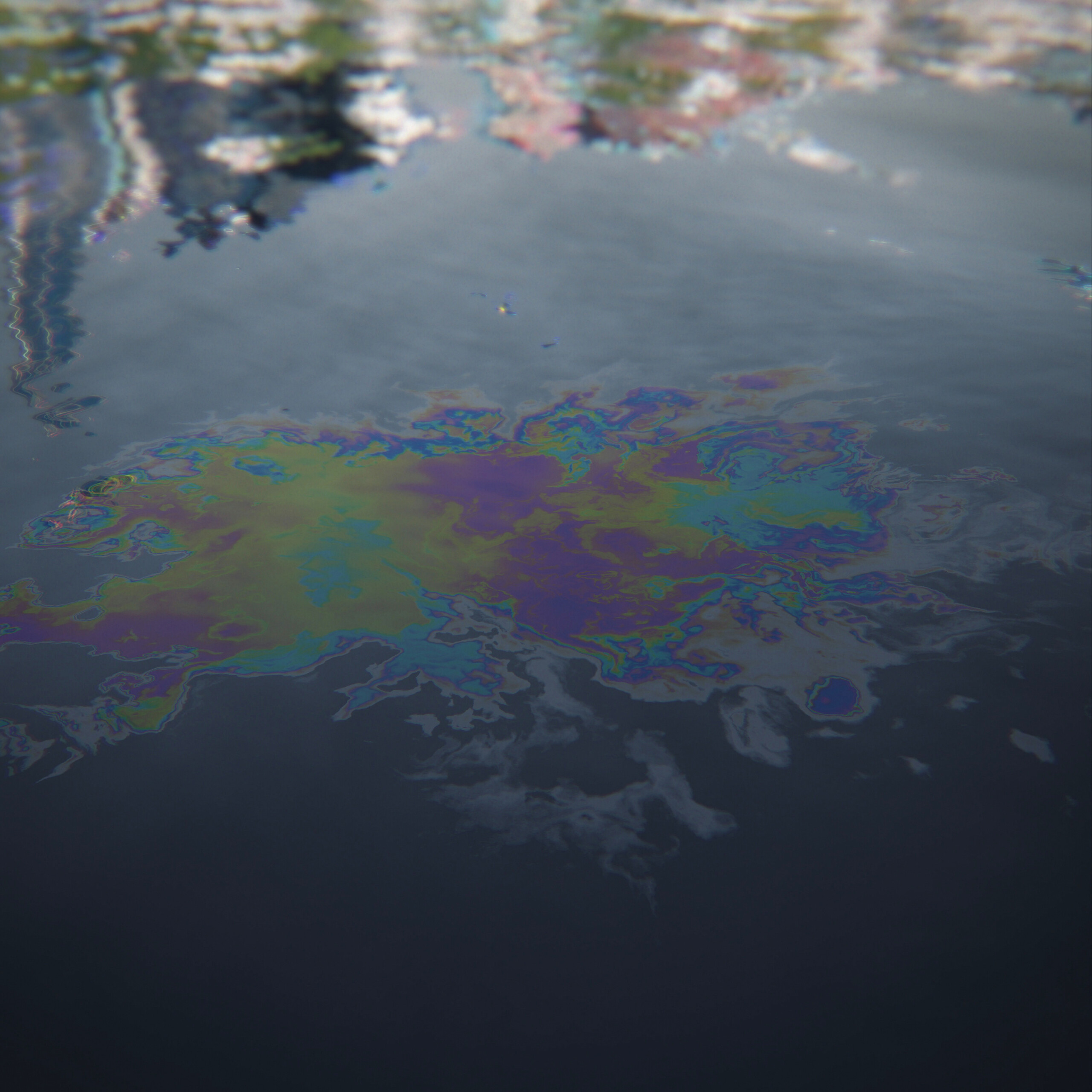

And this is wonderful, too (an LED work stands like a lightbox on the table behind the bread; on its screen is a hypnotic image of a gasoline rainbow on moving water. In the image are reflections of trees, a riverbank, hints of the sky—like all of Gerrard’s images and environments, it’s a simulation based on coded algorithms). What is it?

This is part of a series called Flags. About 14 years ago I’d become interested in gasoline on water. The exquisite rainbows; patches of colour sitting in the street where gasoline has leaked out. Embedded in the petroleum condition is this beauty. But despite gasoline’s allure and beauty, it’s toxic. It’s so dangerous. It just struck me as an interesting metaphor to work with.

How did this metaphor become transformed into a digital artwork?

I took photographs of gasoline on water and I asked my programmer, Helmut Bressler, whether he could look at it algorithmically. He made a basic simulation of water using a thin-film refraction algorithm, a solution from physics for modelling reality. We decided to choose four major continental basins—the Danube in Europe, the Amazon in South America, the Nile in Africa, and Yangtze in Asia. I travelled to each river, discovered a site on the bank of each, documented that site, the colour of the water, the motion –each work is linked to a very particular place. We worked on it for several months and this is the result. It’s virtual; an algorithmic simulation of millions of rays of light hitting a thin film sitting on the water.

It’s poetic, and hypnotic.

This one is the Danube, which really is blue. Each river has its own colour. And gasoline reflects a specific spectrum. It’s a metallic, shiny look.

Beyond the aesthetics, what about meaning? Your work often delves into representations of what drives us, how power structures dictate our lives. Here, you’ve essentially created a beautiful oil spill.

It’s really a rainbow, and I was curious about how the rainbow flag is used by different groups. In some parts of the world the rainbow flag points to gay liberation, but in Spain it’s a peace flag. I wanted to use this particular rainbow to talk of modernity and petroleum; freedom and toxicity.

On the topic of flags, let’s discuss a work that reached millions this year and also deals with petroleum and modernity. Western Flag is a haunting image of a flag of black smoke in a barren landscape, but it was a commission, right?

Yes; I’d done a piece for the 2012 Olympics about smoke, so I had this beautiful smoke sim that we developed. I asked Helmut whether we could take that and stick it on a flagpole. It was immediately powerful. A smoke flag is very specific to the game-engine medium, you can’t make a smoke flag for real. We showed it to Channel 4 (UK TV broadcaster Channel 4 commissions artworks) and they said they loved it. I got the commission, and I had a year to make the piece.

The setting is a depleted oil field in Texas.

We focused the work on the site of the Lucas Gusher. It was the first large oil strike in history, in Spindletop, Texas. Previously to that you had people exploiting oil seeps and small drills on the east coast of America and in Europe—Poland, for example. But on this strike, in 1901, 100,000 barrels of oil flowed in one day, more oil than in the rest of America combined. By 1902 you had an oil city; thousands of oil men fighting over the superpower.

What’s the meaning behind the title?

We’re all oil consumers now—but America was the first major oil power. By the 1950s, America’s relationship to this superpower of oil had delivered a very particular economic hegemony in one aspect, military hegemony in another, industrial, cultural—

America was founded in a modern sense on the mass exploitation of oil between 1900 and 1950s, and I was interested in that as a less acknowledged historical fact.

I also wanted to point to the legacy of that greatest oil strike, which isn’t so much about mobility and comfort, but has more to do with carbon dioxide. A significant quantity is still in the atmosphere. People forget that carbon dioxide is invisible and remains unless it is reabsorbed and recaptured. It’s a waste product of our society. So the flag recalls carbon dioxide. In a sense it’s a carbon flag. It’s a black smoke flag.

How did you make it?

We had to unite three systems: a volumetric sim, and then a turbulence sim, and finally a gravity sim, which gives it its weight. It’s synthetic, it behaves more like steam. It wasn’t plausible at first. It’s one of the most difficult pieces I’ve ever made. We fought that flag for eight months!

And if carbon dioxide is invisible, how did you envision it?

We know what gas under pressure looks like when it’s released from a small jet, but one of our most important resources was this weird thing in America where tractors pull huge objects and they burn so much oil the exhaust is black. We went to Spindletop and photographed the site, we worked on this flag, built it, produced it as a simulation. It was broadcast on Earth Day in April. Channel 4 ran its normal programming, but every hour, twice an hour, you’d lose the program and see this for 20 seconds, 40 seconds.

What was the response?

People were freaked out. They thought it was a terrorist attack. I wanted people to be a little jolted. After that, it was on view in the courtyard of Somerset House as an LED screen in London, it was 7-8 metres wide. And then it was live-streamed on the web for a month. So it was on view for a day … a week … and a month.

Western Flag’s reach also went way beyond that.

Yes, it was picked up on social media, particularly Facebook, and people shared it as a video clip. We had one post that was seen by about 5-6 million people, and shared 50,000 times. It really travelled. Soon after 21 April it was the Fourth of July, Independence Day in America. To some Americans it spoke less of ecology than of a combustion of the national state before their eyes. It burns on. The band U2 just called and they want to use it on their Joshua Tree tour. I’m not sure yet, but I might do this. I’m interested in the public domain—particularly with Western Flag, the focus is on the broadest possible public.

You talk about carbon dioxide and how some viewers were afraid of the flag, but for me it reads as ecological depletion—the Spindletop site in the piece is completely barren.

It was already exhausted and abandoned in the 1930s, although there are still small oil pumps there taking out seawater seeps.

In the past some of your work has been about dust storms, military exercises, data farms, factory farms or solar energy facilities. But this year you seem to be focusing directly on petroleum. In the face of peak oil and the obvious climate change—think of this season’s hurricanes—what can we do?

The problem won’t be solved on the supply side. It will be solved on the demand side. Nobody talks about consumption.

Getting people to really change consumption doesn’t match today’s politics.

Energy and politics are inextricably connected, as are energy and economics. Our conception of history is disentangled from materialist concerns; it’s very unacknowledged how energy influences politics and society. I wanted Western Flag to talk about the disintegration of the nation-state, which is happening before our eyes, and how we have to look at society with a strong relation to material culture, like oil.

Let’s ask some speculative questions. What would our society look like without oil?

I’m not a specialist or an ecologist, but there are a couple of things I suspect. Petroleum is more powerful than people understand. If you look at the highway system, is it petroleum reality … a virtual state of being. If you were to try to produce a highway system without gasoline or diesel power, it would be extremely challenging. Try running an aeroplane on any material other than gasoline. There are big question marks about the hypermobility we’ve become accustomed to.

And it’s not just our own hypermobility.

es, we can consume in a particular way because food is so mobile, too. Prior to the twentieth century, famines were commonplace. Food couldn’t just zip around. Without gasoline you’d have to relocalise energy sources—local energy being the sun, wind and water. Ireland closed all its water-powered mills in the 1950s; I would imagine that in the absence of gasoline, demand for mobility would have to be reduced. And people would have to eat less … and probably better.

Might these ideas crop up in your art?

Most specifically, in that kind of Beuysian tradition, I’m interested in a broad public, and I’m interested in consumption. As an experiment, even for ten years, to work on an art project that deals with local energy, discourse, experimentation and even food, is a good challenge. I do have an idea for a relocalisation of agriculture. You generate electricity locally and run a kind of Art Farm. It’s about drawing a line and rejecting petroleum. It’s in its very early phases and I may not ever do it.

It would perhaps be a return to, or a creation of, a certain reality. What do you think of our current reality?

The reason I work within simulation is, one of my core senses is that we now exist in a virtual state. Modern society is a petro-state. Petroleum has completely distorted everything–food markets, everything. And it’s synthetic to the point in which it could be considered a simulation. (John shows me a heavy metal object, a curved sculpture that’s dense, but small enough to fit in both hands. It is a factory component from an alternate-current hydroelectric plant in Telluride, Colorado, built in the 1890s and based on Nikola Tesla’s concepts)

Look at this. It was a miscast. Its form is really of the body, isn’t it? It’s like brains or balls or breasts; it’s fantastic.

If we’re talking about energy, the name of Tesla has been revived by Elon Musk and his electrical car. But the ideas of Nikola Tesla, the man, were intriguing. His great invention was the AC electrical generator using hydropower. The first application was in Telluride, Colorado, and it went on to Niagara Falls. But his dream of an electrical society was drowned by gasoline by 1910. By the 1920s and 1930s the idea of running a factory on water was hilarious.

Why? Is water power that impossible?

Petroleum is so much more than the broad public gives it credit for. It’s tens and tens and tens of millions of years of sunlight. It’s the most extraordinary power source, a superpower. It’s mobile. It’s dense. There is nothing more powerful than a litre of jet fuel, in calorific output terms. Water power couldn’t compete.

But could it now? Are you an optimist or a pessimist?

I’m probably a pragmatist. It seems unlikely that in the next 50-year arc that we won’t have this abundant power supply—but at the same time I don’t want to be complacent and have a mindless relation to energy. I’d like to develop a more evolved social consciousness, and the core is that we have to stop burning petroleum right now. We still have enough.

As long as we’re stuck in petroleum culture, are you, as an artist, looking for moments of beauty within it, as well as using that beauty to critique?

There’s a lot of beauty in contemporary conditions, and I’m not denying the things that are possible now. I’m not a pessimist in that sense. To answer your previous question, I’m optimistic, and proactively speaking about issues about beauty and ecology and things that interest me. But I can’t get away from subjects like a 50 percent drop in biodiversity globally since 1900. In that light, Western Flag is a flag of mourning for the great die-off that’s called the Anthropocene: plastic in the ocean, radioactivity, isotopes in the land. But what it really points to is human change.

The works have a quality of being sublime, but almost a toxic sublimity. I do think we will burn all the gasoline. We’ll come to some kind of crisis, and it’ll definitely be challenging for the human project. These works point to that, not in a celebratory sense but as an inevitability. Western Flag is a gasoline flag for modernity. We all live under this flag. You and I do.

John, thank you for talking to us.

Installations

WORKS

Flag (Danube), 2017

Flag (Danube) is one of many simulations of gasoline spills atop major world rivers that Gerrard has produced (the others in this series being the Yangtze, Amazon and Nile). Based on documentation from site visits, each river is simulated via algorithm to match orbital and diurnal conditions over a 365-day period. That means seasons and days are visible, but not weather conditions, or, for that matter, gallery opening hours. The viewpoint swerves, the waves are animated, the effect hypnotic and unsettling: a rendering of pollution as an uncanny beauty. Gerrard’s art pieces generally connect to real-life sites. The final art piece (which is essentially lines of code) is presentable on both smaller LED boxes or larger screens on view around the clock.

Western Flag (Spindletop Texas), 2017

Western Flag–a simulation of a “flag” made of black smoke streaming from seven nozzles atop a thin flagpole, superimposed on the barren oil-field landscape of Spindletop, Texas–was a commission by British TV broadcaster Channel 4. The piece was broadcast as a television intervention at irregular intervals on one day on April 22, 2017 (Earth Day), then erected as a large-scale LED-screen sculpture in the courtyard of Somerset House in London for one month. It was also streamed online and reached millions of people through social media. Spindletop, Texas was the site of the first major American oil gusher, and, according to Gerrard, was a birthplace of modernity in material and energy terms. Western Flag reads as a warning, a mourning, an interstice between reality and fiction.