Human Beings are the Solution

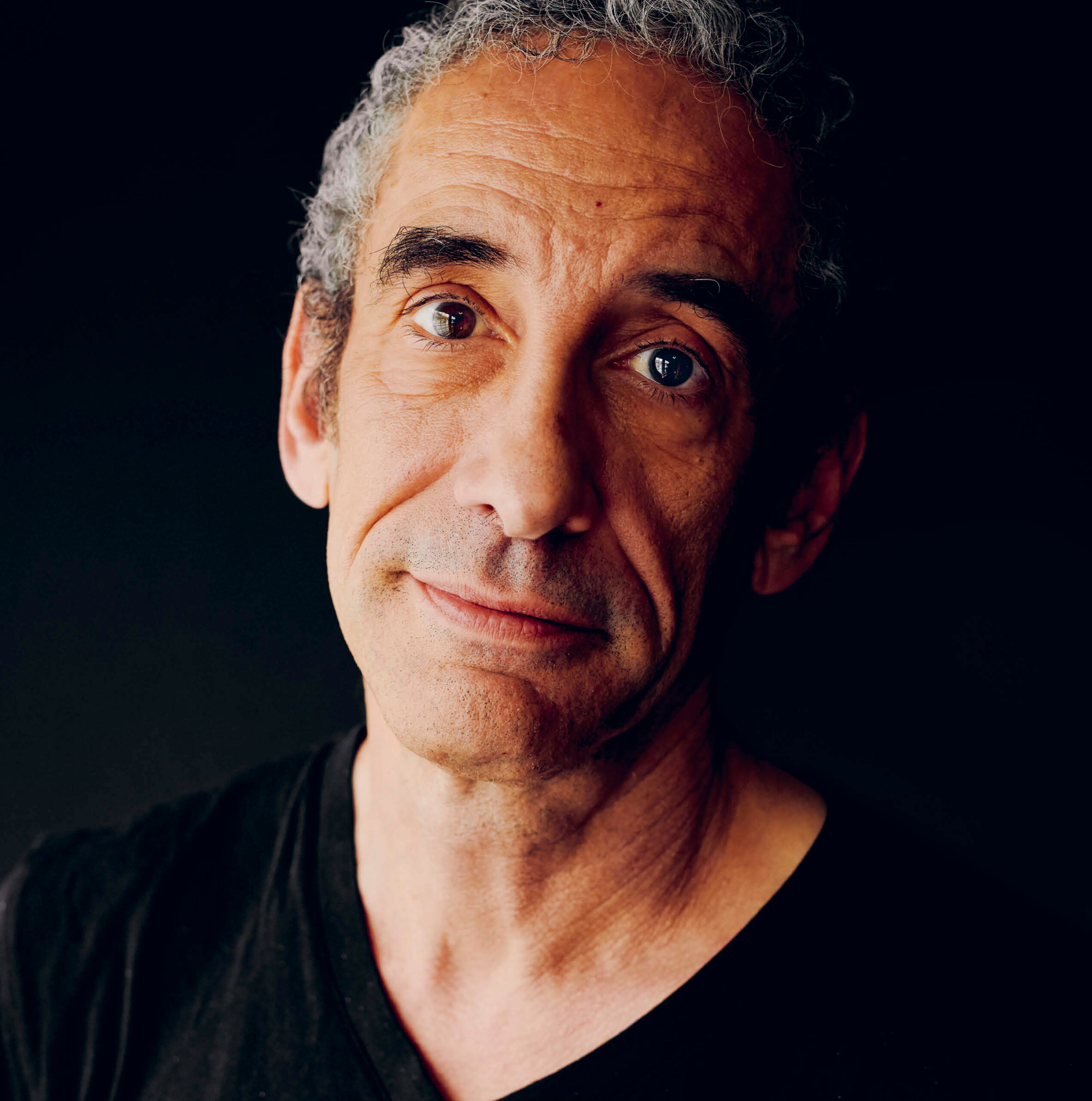

Douglas Rushkoff

DOUGLAS

RUSHKOFF

Some say that in the near future, superintelligent computers and artificial intelligence will be able to control human lives more than ever before. Others believe we are decades away from that evolution.

But what we can prove is that humanity and human interaction have been affected, virtually in their entirety, by social media and platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube. People have started to live and communicate in their individual reality tunnels, and a significant amount of them are no longer able to communicate normally. Scientists, industrialists, sociologists and media critics have opened up a discourse about what happens when social media and the internet affect our potential in humanity and liberty and dramatically speed up our lives. One of them points out how humankind is still a major issue within this digitally and technologically evolved world.

“When things begin accelerating wildly out of control, sometimes patience is the only answer. Press pause”, Douglas Rushkoff once said. The American media theorist, writer, columnist and academic is known for his connections to early cyberpunk culture and his encouragement of open-source solutions for social problems.

In 2002 he was awarded the Marshall McLuhan Award in 2002. Rushkoff has published novels and non-fiction and has taught at numerous universities. He is currently Professor of Media Theory and Digital Economics at the City University of New York, Queens College. Douglas Rushkoff and I held a conversation in two different time zones to discuss human life in the digital age and his upcoming book, “Team Human”.

During my preparation for our conversation, I came across an interview from two years ago with you by the editor of The Verge, Paul Miller, about one of your last books, The Present Shock. When everything happens now. At the time, Miller had been offline for more than 300 days. Unfortunately, we cannot meet in person and we’re talking through Skype right now, so for us being online is inevitable. In what situations of life should we be more offline?

D

R

I think some of the things that work really well offline are having sex. That works well in the body. And being with family. Pretty much anything that you can do in the physical world. You get more bandwidth when you do so; you get an additional sense, whether it’s touch or smell. You see a lot more when you’re with the person in the world. I would think it’s hard to think of what works better online. I guess if you want to be speaking to a million people at once, that works better through media than trying to gather everybody around you. If you’re trying to avoid flying in planes, you can communicate with people far away. But I would argue it’s never better, it just allows for telepresence. You know, when you’re using it to do something you can’t do in real life, that’s cool. But if you use it instead of real life, you miss out on something. You miss out on certain levels of honesty and experience. And I guess it has to do with what your values are—whether you’re living to promote your utility value or your value as an employee, your monetary value to some company. Then it could be that being plugged in, and interacting with people you know that way, is better—but you lose. It’s the time of your life that you’re spending, and you know how you want to spend that.

-

-

-

-

So you say that it’s essential that we maintain our human autonomy in this digital age. But how do we keep human sovereignty both now, and also in the future? How can we avoid becoming nothing more than slaves in the digital age, and instead use the digital world to help us?

D

R

Well, I think the first step is being conscious. For people to be aware when they’re using a digital platform, and to be aware that the platform has been programmed by people and companies with very specific agendas in mind. It’s not a conspiracy theory at all. It’s just saying that the tools that we’re using were made by people who want something—whether they want us to be a subscriber or to be dependent on the tool, or to engage with other people in specific ways. The tools will encourage certain kinds of behaviour and discourage other kinds. So we need to be aware of what the tools we’re using are actually for before we decide to use them. If you look at something as simple as Facebook, you think what is Facebook, above and beyond what I am using it for? The platform is there to extract data. Mainly consumer and political data about me.

The kinds of behaviours it is going to encourage are data-rich behaviours, behaviours that have to do with my consumer choices or my political choices, different things about my lifestyle that can be monetised as categories that matter to them. But the sorts of behaviours that say: Get me to connect with people in the real world; the sorts of behaviours that push me offline, that encourage me to keep certain things about myself private or limited to my intimate friends—those will be discouraged, because they don’t fit the business plan of the platform. So I think that’s really the main thing. If people understand what the technologies they’re using are for, then they’ll be less likely to be used by them. They are more likely to choose to use them for purposes that are aligned with the purpose of the platform, rather than trying to get love, or satisfaction, or a sense of self, or genuine social connections through technologies that aren’t built to do that.

Please select an offer and read the Complete Article Issue No 6 Subscriptions

Already Customer? Please login.