C. G.

Boys

Collective Dreamer

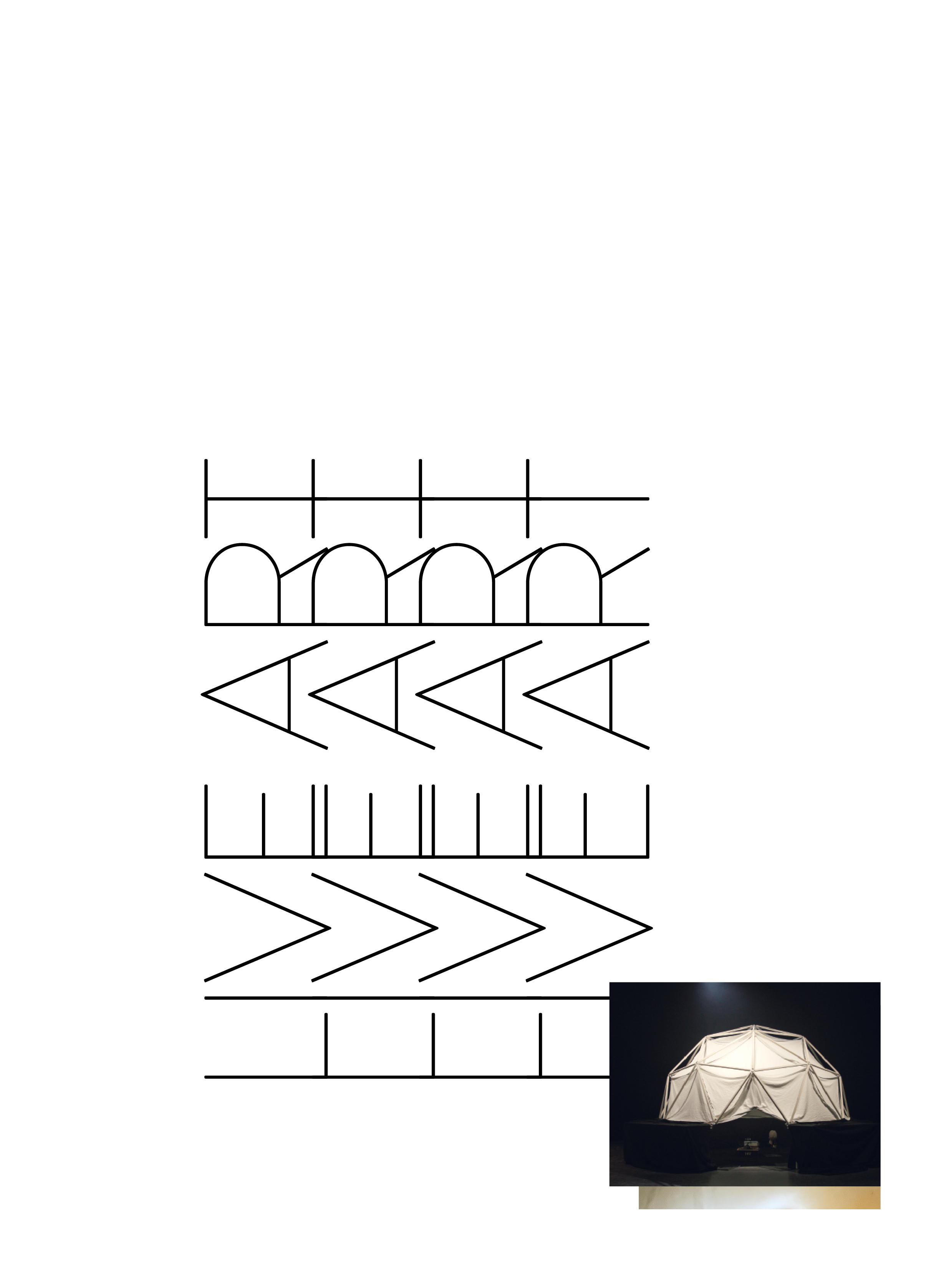

What happens when two computer scientists team up with two directors and, just for once, don’t launch a start-up? This is art that kindles a digital campfire using the latest AI tools. The live performance The Collective Dreamer turns the audience into active participants, who share their latest dreams and, after a few moments, see their individual images incorporated into a collective dream projected live across the roof of a tent. So what does Berlin dream? What about New York City? Or Beijing? And what actually are those shadow images conjured up by the AI on the walls of the collective cave?

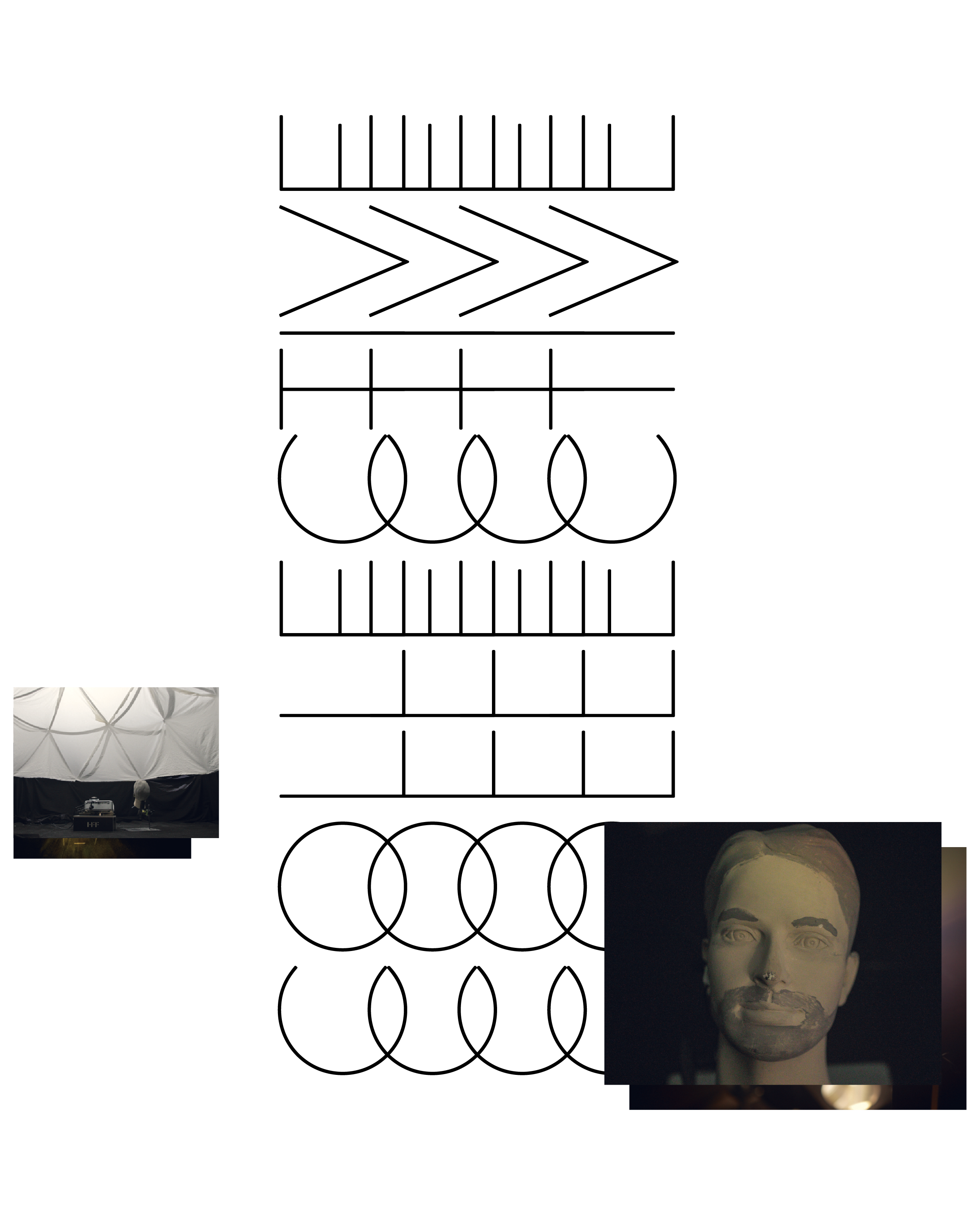

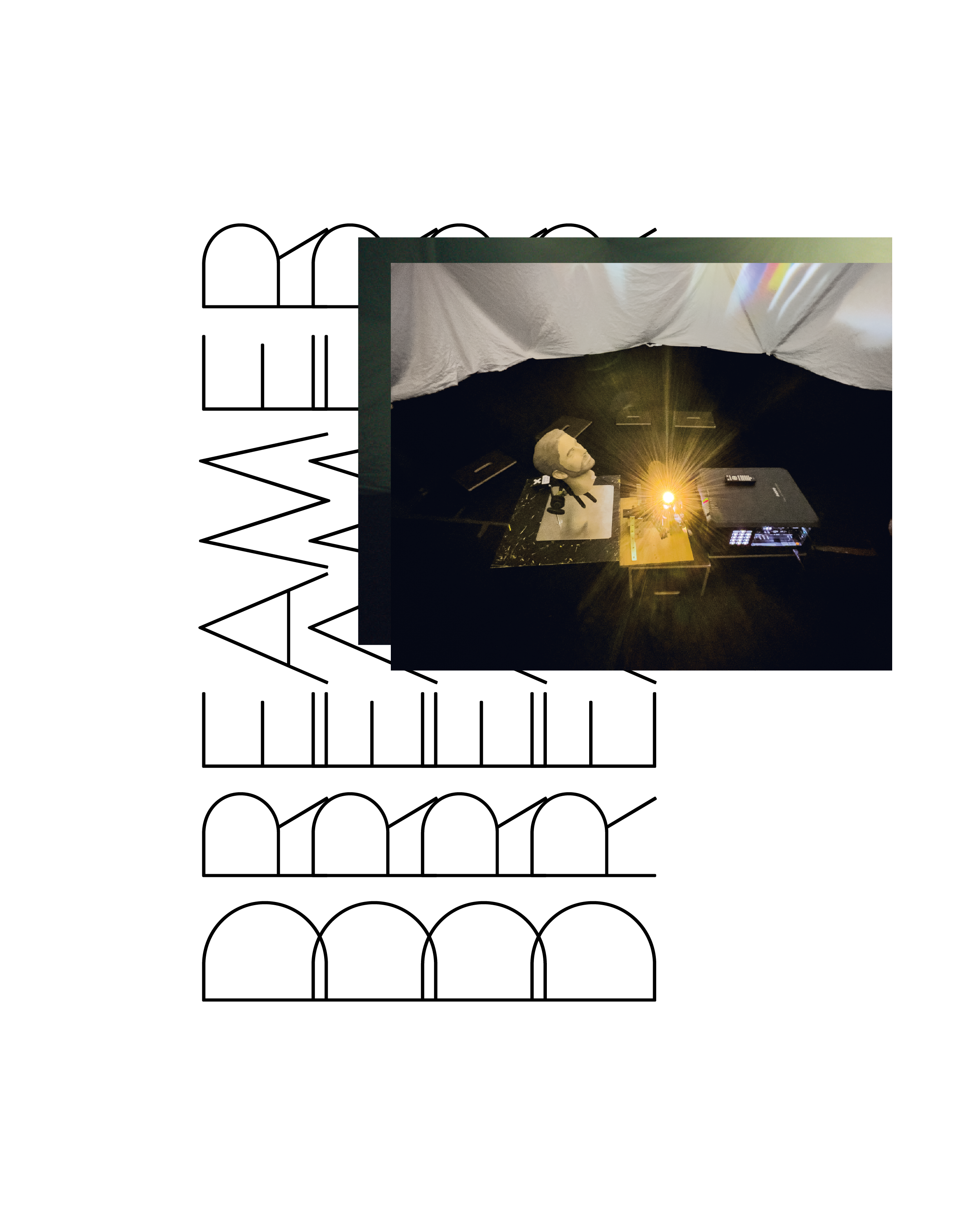

The eyes take a moment to adjust to the darkness. Inside the tent, light reflections flicker across the domed roof. The audience enter and take up their places in a circle as sequences of images dance above their heads. Figures occasionally emerge; a spider crawls across the canvas, vanishes again, reappears. There’s a magical feel, like a tribe of hunter-gatherers assembled around a camp-fire to listen to stories. New arrivals whisper into the ear of a stylised head in the centre, describing their most recent dream, or what they can remember of it: sequences, fragmentary images, situations. After a few minutes these new images actually appear, woven into the shared tapestry of dreams, in which the contributions from all present are translated into images by the AI. The result of this combined effort is a sensuous, almost hypnotic experience with a magnetic pull that few can resist.

People embrace the performance, invested in it as participants; some stay for two hours or more. When the art project The Collective Dreamer premiered as part of the programme of events accompanying the Munich Film Festival, 60 visitors came. By the time of the Kunstareal-Fest in Munich’s art museum quarter, there were 200; young and old, film fans and chance passers-by who were spontaneously drawn in by the walk-in installation space. This shared performance, this joint effort, is the focus. But for computer specialists Eduard von Briesen and Ronny Kohlhaus and young film directors Moritz Schlögell and Luis Sütter, there is more at stake than simply retrieving images from the audience’s subconscious and using speech recognition and prompts to convert them into sequences of images. Their goal is to uncover the AI structures underlying the process, the images that were clearly used to train the machine. Given time, these structures inevitably reveal themselves. The project currently encompasses 10 hours of material at a resolution of six frames per second. Adjusted to cinema specs of 24 frames per second, that’s equivalent to a full-length feature film of two and a half hours.

Flooding with images

So how does Munich dream? The four digital performers are sitting in the garden of Munich Film School talking about floods of images, popular recurring characters, nightmares, and the rule that children must be accompanied by an adult. Four young men who make no effort to play down their enthusiasm about the project. They describe audience members staring mesmerised at the film generated by their own minds. They talk about the black box of dreams and their largely intuitive approach, despite the array of technology they use: AI programs like Whisper (to translate spoken language into text) and Stable Diffusion (which converts text into images using prompts—descriptions of image contents, preferably precise) plus a pinch of OpenAI’s GPT-3.5, known as the modern oracle and a competitor for old-school search engines.

At the start, they found they had a bug that gave a redder and redder cast to the projected images, intensifying the impression of a foetus in the womb. In fact, the tent does feel like a sanctuary; minutes pass as if in a trance. The Collective Dreamer clearly triggers something in us. But what exactly? What kind of inputs does it need to do so, and what form do they take? If 20 people go in and say: I dream about flying, the program might eventually come up with an aircraft, says Moritz Schlögell. But vague inputs are unhelpful for AI’s visual feedback. We have to provide some direction, as a basis for the machine to generate its hallucinations or dreams. It works best with images that frequently crop up in the data pool. Like Father Christmas, or Batman. Every new input causes minor changes, and older inputs are dropped. Or they mix and blend, creating a heart, say, from the input red, possibly followed by an open chest wound. These are all associations that we are no strangers to. It’s astonishing what can be thrown up by a few prompts. But the real highlight comes when all the individual voices are linked together into something truly great, says Ronny Kohlhaus. Instead of simply creating strings of prompts, the single voices blend and merge into a new and perpetually changing dream. The inputs from all the installation’s visitors are swirled into a constant procession of new images. No longer single sequences, they come together into a new whole that, in turn, provides the seeds for the next dream. All these inputs combined form a kind of subconscious, a fertile ground from which images grow. What we see at night is a—heavily diluted—reference to our first dream in the morning, says Eduard von Briesen. Could there be a more poetic expression of technology?

Please select an offer and read the Complete Article Issue No 15 Subscriptions

Already Customer? Please login.