Slow Down

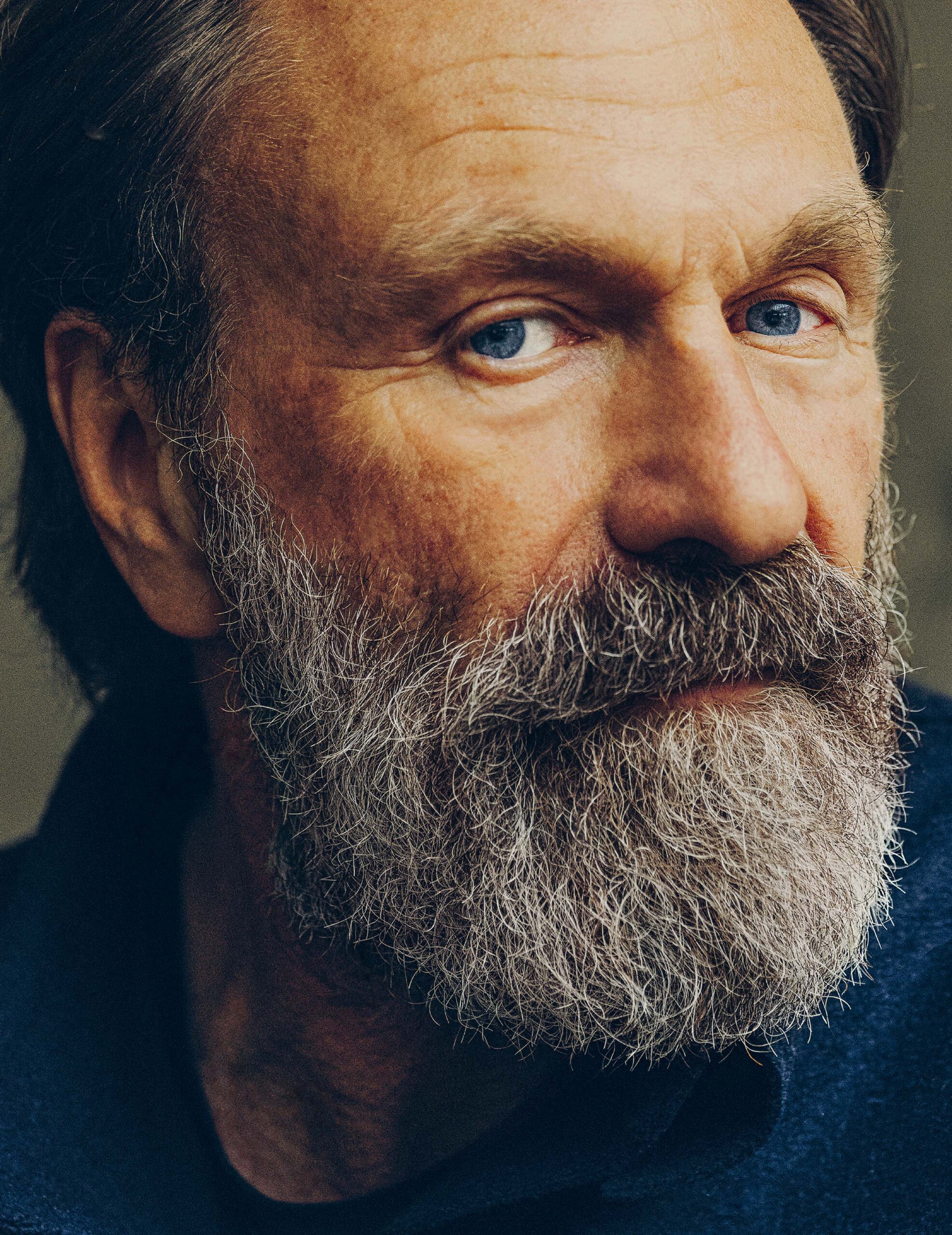

Claus Sendlinger on slow travel

It’s mid-afternoon on an unusually sunny day in Berlin, and Claus Sendlinger sits at a communal bar in the offices of Slowness, his latest company, in the city’s eastern district of Rummelsburg. Stylish people eat pastries and drink tea from handmade clay cups. Minimalist design pieces dot the space; mood boards hang on the walls. At an elongated table, other employees work on laptops. This place is part of what Slowness calls the Flussbad campus, a sprawling multi-building ensemble on a plot stretching from a busy street to Rummelsburg Bay, where Berlin’s Spree River expands to the dimensions of a small lake. To the street is a construction site; the structure we’re in is a repurposed former port authority building. To the other side, visible through windows facing the river, is an unusual structure that’s already made a splash in the German capital’s cultural scene—the Reethaus, a temple-like edifice rising in a vaguely pyramidal shape to the sky, its roof covered with the thatched straw reeds (Reet) it’s named after.

The Flussbad campus is part of a greater concept for how to bring people together in the future—one that connects design, land, and community, all with a dash of mindfulness: “I’ve traveled a lot to hotels in the world, like Château La Coste (a French wine estate) with its incredible sculpture park, but I’ve also always been into festivals like Burning Man (the huge desert festival) and Wonderfruit (an environmentally focused arts gathering in Thailand). We thought this place should have a similar quality, which already makes it very unique in Berlin,” says Sendlinger.

The construction site is a four-story concrete structure and will soon become a hybrid property including hotel rooms, advanced holistic health facilities geared toward performance and longevity, a coworking space with three-meter ceilings, and Slow Lab, a campus meeting place and showroom for new ideas in health and hospitality with an “elixir bar” offering a restorative, nutrient-rich menu. The campus master plan was conceptualized by the acclaimed Berlin--based architect Arno Brandlhuber. Upcoming along the waterfront is the Bootshaus (boathouse), planned as an all-day restaurant, members areas and other spaces dedicated to health and gastronomy—a rethink of the public baths that once existed here and were used a century ago by as many as 10,000 working-class Berliners each day. Throughout it all will be opportunities to learn—about crafts and cuisine, about health, healing, and longevity, with workshops, courses, and events aimed at addressing global challenges through personal and professional development.

Already complete and in operation is the Reethaus—a building designed around contemplation and clarity by Austrian architect Monika Gogl—which has already anchored itself as a sanctuary for unusual experiences in sound. “It’s like walking into a sculpture,” explains Sendlinger. The trapezoidal main space soars to a James Turrell-like skylight. In it, a 360-degree spatial sound system has already created a sonic backdrop to curated auditory events featuring, for example, Chinese artist Pan Daijing or seminal independent filmmaker Jim Jarmusch, both presented by Reethaus curatorial partner Soundwalk Collective (a renowned sound art duo), and an event featuring hours of recorded throaty, ethereal chanting by Tibetan monks. Being here is like visiting a sacred temple—guests take off their shoes and lie down on tatami mats to take in reverberating sonic baths; when they leave, it’s as if they’ve been thoroughly cleansed of the troubles of the world. Around the center space, a series of rooms evokes a Japanese feel: sweeping floor-to-ceiling windows erase the boundaries between indoor and outdoor, birch trees grow in indoor atriums, materials everywhere, like wood and concrete, are natural or subdued.

Please select an offer and read the Complete Article Issue No 16 Subscriptions

Already Customer? Please login.