How we've shaped the land, and how it has shaped us

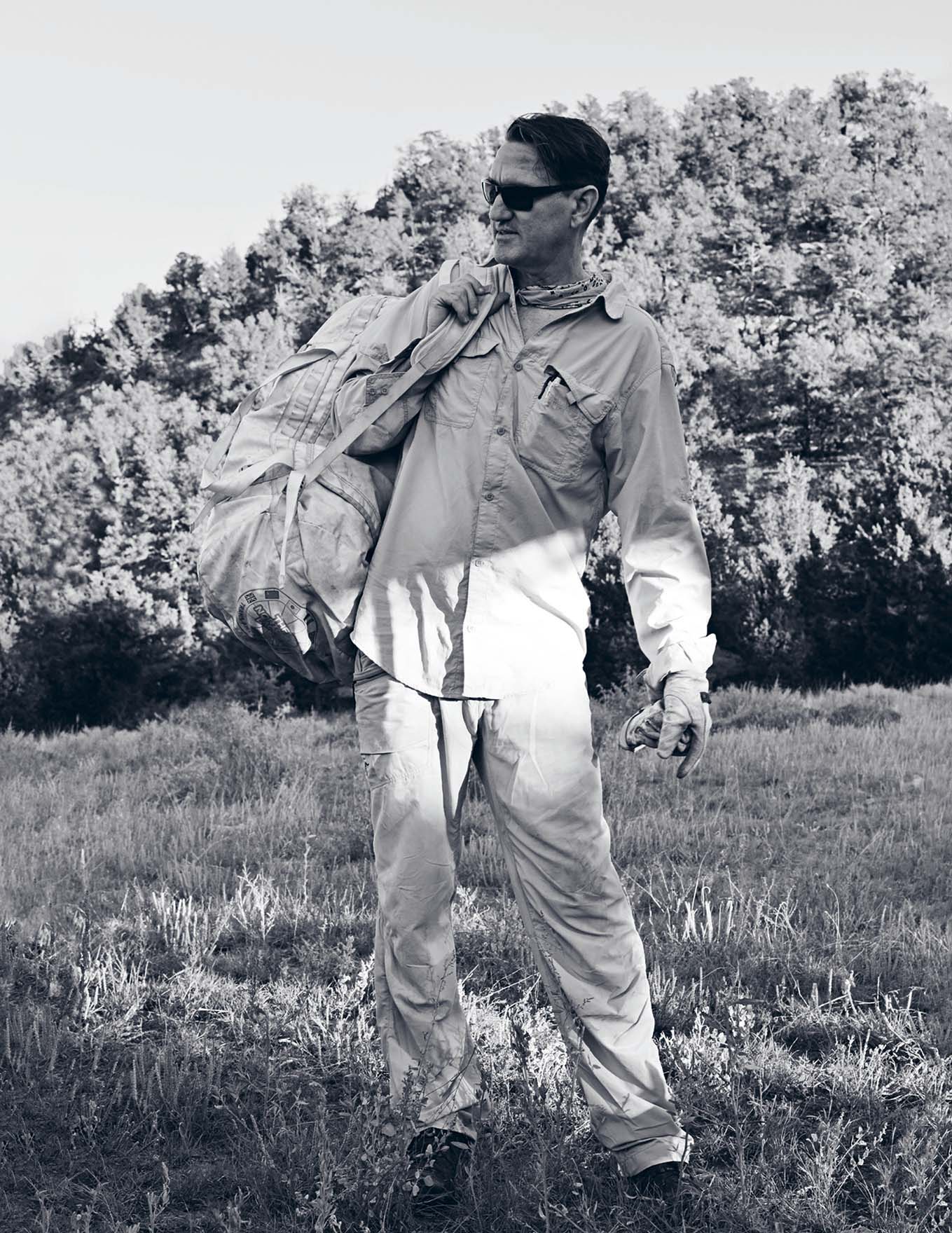

Chris Taylor

The first trip taken into the wild by the director of the Land Arts of the American West program, Chris Taylor, with his students was in 2002. Since, it has become a long-serving field program that he runs out of the Huckabee College of Architecture, Texas Tech University. In the New York Times, Taylor explained it as a study of “how we’ve shaped the land, and how it has shaped us.”

Every year is a different experience.

For two decades, Taylor and a group of students have left Lubbock, Texas, at the beginning of September for “a semester abroad in our own backyard,” which is essentially a carefully curated itinerary, an immersive experience that changes people’s lives and forever alters the way they view things or how they relate to time passing. Dedicated to the “intersection of human construction and the evolving nature of our planet,” they travel 6000 miles overland while camping for two months to experience and live next to major land art monuments such as Robert Smithson’s SPIRAL JETTY in Utah; Walter De Maria’s THE LIGHTNING FIELD in central New Mexico; Nancy Holt’s SUN TUNNELS, also in Utah; and Michael Heizer’s DOUBLE NEGATIVE in Nevada. In addition, they investigate land use such as pre-contact archaeology, military-industrial infrastructure, and uranium waste.

No one comes back the same.

I traveled west with Taylor and ten peers to experience land art in the fall of 2019. We visited 21 sites and encountered more than 30 field guests across five states. Coming from Europe, I viewed the American West as symbolic, mythical, and iconic, with a heart of guns, cotton, solitary men, cacti, and dunes. However, as we traveled through the land, diverse layers of delicacy and weight, sophistication and profoundness materialized before me. While artists and writers in situ are not unusual, there seems to be an urgent need for artistic immersion, me included. In its advanced stages, it is about teaching reality as a discipline, fostering the habit of attention, probing depths of inquiry, and creating an understanding of human actions that shape environments, preventing creatives from becoming detached from the complex ramifications of places.

The land is real.

“Ding ding ding,” Taylor is calling us from afar. We crawl out of our tents. Men and women appearing in boiler suits, work trousers, boots, and sunhats. Slowly, we assemble to eat, drink coffee, and refill our bottles. The whole camp rumbling. Traveling in two pickup trucks and a van, we set up a communal kitchen and shelter at every site. Meals are cooked and shared, daily seminars and screenings are held in the open air.

Time is finite.

About twenty days in, we are reconciling. Most of our platitudes are now gone. The place is dusty, the sun is blazing hot, and there is nowhere to hide. Everyone is weather-beaten; we know that. And that is the way it is. We are happy about it. In a world ruled by wind, water, and sun, we build a kite and wrap the wind into a parcel in the air. What could it do as an earthwork, being strapped to the gust? We want to be in nature, experiment by letting ourselves be held by the wind in a great and overwhelming exercise of becoming immersed.

We meander.

What we have is a home, a studio, a classroom, a lab in the desert. But it goes further than that; it occasionally become a disco, the best bar in the neighborhood, and the local library. Of course, none of this is permanent, but the bond between us and nature creates constant facilitation, liberty, activation, and play. We are spinning in our orbits, thinking about how to record, track, trace, experience, and get the most out of time when it is used as a material. We are working with what we have, and that is the exercise. Traveling is becoming our methodology. Now, some years later, that method is still a fundamental part of my practice.

You began the Land Arts of the American West program through the device a semester in our own backyard. Tell us why getting out of the classroom, out of your comfort zone, and into the wild is essential.

C

T

There are a couple of ways that I would approach that question. One is as an architect: the way the world connects with architecture tends to be way more complex than we’re able to initiate through aspects of reading. I mean in a context where complexity is not an abstraction, but a present reality that we live with.

Traveling allows us to appreciate that complexity in an embodied or direct way, which is different from staying on campus in the classroom. In thinking about how we pay attention, we find ways to expand rather than contract. That only becomes possible when you venture out. And part of that is that you are giving up control.

Traveling as a method is an appreciation of complexity. It comes from living in it, from direct experience. And I don’t by any means claim that spending four days at a place makes us understand the totality, but it opens the door to the possibility of being present.

-

-

-

-

As an architect, how have you been inspired by methodologies from social and natural sciences and their literature? I remember you reading Barry Lopez’ Horizon on our trip.

C

T

I would like to answer it in terms of: yes, this was part of a grand plan. But the honest answer is all about allowing one opportunity to open and expand another. It’s about making connections, being receptive, and following opportunities. I feel very fortunate to have had the time to know Barry Lopez and for his world to intersect with mine.

If I trace back my steps, there’s a pattern that reaffirms my passion for practical learning. When I was a senior in college, one of our classmates came up with the idea to do something different and build it there and then. In a matter of hours, we crafted and built the idea in the studio. There was this huge lightbulb moment and an attractive proposition for me: we could make the architecture that we're thinking about.

There’s a direct line to this embodied way of learning, of teaching through living. What we do with the program is not to eliminate our disciplinary specializations, but to build an ecosystem of expanding connections. What we bring back from our travels is not stuff but awareness, connection, narrative, and possibility.

-

-

-

-

You often talk about the importance of the state of saturation. Tell us about what spending prolonged periods in the field does to the learning. What is the difference between seeing Double Negative and living in it for a week?

C

T

It is about what we are paying attention to and how we pay attention to it. There are larger patterns at play right now, conditioning us away from deep looking, training us to pay attention to things that last no more than 30 seconds.

In contrast, I want to create a method for deep connection, where you can be aware of the sun’s rising and setting or whether clouds obscure it. That is a rarity in today’s life. And saturation enables a shift in that sort of attention. We can be exposed to things that make us uncomfortable or unpleasant, but we're going to be saturated. It has all the intellectual components, muscle memory, and full bodily recognition.

When we visit Double Negative, we’re there for almost a week. We see it not just as an artwork, but as a place; it is a setting, with perspectives moving from abstraction to figures in dialogue. I would hope that part of what's happening is us allowing for the settings to be present, to be alive, to be dynamic, and not just a freeze frame or a snapshot.

-

-

-

-

The art of immersion is a hot topic today. Part of your teaching is about seeing, making the invisible visible and vice versa; how do you teach the complexity of complete immersion?

C

T

That is fascinating: in your first question, you didn’t ask about immersion; you asked about saturation. And to me, that is a pretty powerful lens through which to think about it. For instance, William Gibson’s Neuromancer is projected to become saturated in cyberspace. You leave your body and enter the net. It’s about the journey. Or we can think about it in terms of duration.

I like this idea of creating a situation where we go somewhere but have yet to determine what we should look at. You’re going to wonder why I’m not telling you what there is to see, but it’s strategic—to allow you to decide what’s most important. And if you think about immersion as an educational model, the teacher is not defining the outcome. The experience is what we’re trying to master.

A cat is different from a zebra, and that’s fine. But this model deliberately does not teach you that, because it’s trying to present other possibilities of awareness, to create the conditions for the participants to have more agency and be in control of the narrative. In that way, I see my role as a facilitator. Yes, there’s choreography. Yes, it’s a curated list. But it becomes its ecosystem of production. In that way, travel as a methodology becomes more alive.

-

-

-

-

There is a robust, honest, and illustrative metaphor when you say traveling is like being at sea. There is no pause button. How do you work with the commitment to the journey as a tool?

C

T

We’re traveling together, and there is no escape. You couldn’t leave somebody at a bus station even if you wanted to. In all moments of resistance, we take a breather and acknowledge what is happening. This is another way to think about saturation; it’s persistent. We know there’s no walking away, and if we extrapolate this to the human condition, at no point, regardless of our coping mechanisms, do we ever stop being human on this planet. There’s no escape from Spaceship Earth today.

I often talk about the program through the pedagogy of weather or the sea. What I like about that is it’s giving over to learning from something dynamic and constantly changing.

-

-

-

-

Please select an offer and read the Complete Article Issue No 16 Subscriptions

Already Customer? Please login.