NEW

COMMUNITY

Aric Chen

The garden is far more than a green space. It is a metaphor for care. Its cultivation is an expression of civilisation—but also of coexistence, rather than antagonism, between humans and nature.

The garden stimulates the mind and the senses. At the same time, it grounds us. We are embedded in a natural environment that has the potential to lead us to a better life. Green living spaces are understood and used as free spaces. Aric Chen is acutely aware of this. He acknowledges the multi-faceted dimensions of the garden and knows how the voices of plants and animals can determine the actions of governmental organisations. As director of the Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, he is responsible for an institution that not only oversees the historical architecture archives of the Netherlands, but also looks to the future and connects analogue reality with the possibilities of digitalisation. As the first Zoöp in the world, the Nieuwe Instituut has appointed a spokesperson for all non-human species. A conversation with Aric Chen about plurality, togetherness and surprise.

In cooperation with the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, you conceived the exhibition Garden Futures: Designing with Nature, which can be seen until 3 October. Why is the garden so significant today?

A

C

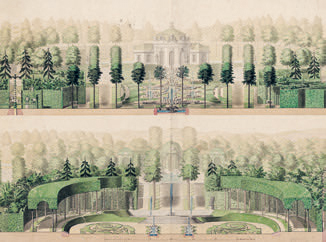

Looking at the world as a garden is super relevant. Gardens are expressions and manifestations of our relationships with nature. Because if you think about how our impact has changed the planet, the world is in fact our garden now. We need to take better care of it. The historical garden could be seen as a manifestation of this paradigm, where we felt we had to control nature rather than live with it. And this has basically led us to ecological disaster. In the past, gardens protected us from nature. Now the question is who needs protection from whom.

-

-

-

-

The perception of the garden has changed considerably over the decades and centuries. What does this tell us about ourselves?

A

C

It is really fascinating to see old gardens and understand what they say about how our relationship to nature has changed. We are living in a time when we should be looking at different cultural constructions of gardens and nature. We’re trying to include indigenous practices and knowledges in our thinking about gardens. Also, we’re trying to look at different political and ideological uses, such as guerrilla gardening—an idea that emerged in New York City in the 1970s, when people started throwing seed bombs into urban wastelands. We want to go beyond the highly mediated twentieth-century image of the garden that many of us have in our minds, with a suburban lawn dotted with deckchairs and swings.

-

-

-

-

Today, the perception has changed completely. We accept that a garden need not only be neatly trimmed, but can also have a wild appearance.

A

C

It is so lovely that we are holding this interview in a garden designed by Piet Oudolf. He did a lot to change the perceptions of what makes gardens beautiful. I think in a different time, let’s say 20 years ago, if we had come to this garden, people would have said Ugh, they should take better care of it. Flowers are blooming riotously everywhere, and there are all those brown, withered grasses over there. That would not have been the image of a maintained garden not so long ago. And yet it’s a beautiful garden.

-

-

-

-

You said that the garden can also be seen as an allegory of human activity: little steps are important in the garden, not only the big master plan. A system of trial and error in order to achieve small improvements.

A

C

I think we have to break through the modernist paradigm of linear progress (laughs). We are totally caught in this trap where we think we are going forward, but it just sets us off the cliff. It would help fundamentally if we would think in a more circular way. In the exhibition, there is a section called The Garden as a Testing Ground. But we—that is, the Nieuwe Instituut as a cultural institution–can also become a testing ground for society.

-

-

-

-

Could you explain that in more detail?

A

C

Cultural institutions have done a good job in being places of debate and discussion, asking questions and raising awareness. But I don’t think that’s enough any more. The question is: What can we do? Can we become a testing ground for society? We don’t just exhibit new ideas and proposals; we also try them out on ourselves. By using ourselves as guinea pigs, we can at least try things out on ourselves. And we do it in public, and we see and show what we learn so that the public becomes part of the experiment. It’s about more than just talking about this idea. It’s about saying: Let’s do it.

-

-

-

-

Last year, the Nieuwe Instituut became the first Zoöp in the world. What is behind this concept?

A

C

Zoöp came out of an exhibition we did four years ago to mark the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus in 2019. It was an exhibition that called for new approaches that would be more relevant today than repeating what was thought a century ago. It asked the question: What are today’s radically new ways of thinking? This resulted in the concept of Zoöp, developed by one of our researchers, Klaas Kuitenbrouwer, in collaboration with many others. It’s essentially a framework for including non-human interests and voices in the decision-making process of an organisation.

-

-

-

-

What is the objective?

A

C

Ultimately, the broader aim amongst other things is to increase the life-carrying capacity of our building and site, while lessening the impact of our activities—such as materials for exhibitions and so on—on broader systems. This picks up on a lot of ideas that are floating around, like rights of nature, indigenous knowledges and more-than-human perspectives. The idea is to go beyond the humancentred worldview and embed that into an organisational framework. This model has been designed to be adaptable to any kind of organisation, public or private, large or small. An entire country can be a Zoöp. In practice, we have appointed a Speaker for the Living, who now represents non-human interests on our board of directors.

Please select an offer and read the Complete Article Issue No 14 Subscriptions

Already Customer? Please login.