CARETAKER

OF

NATURE

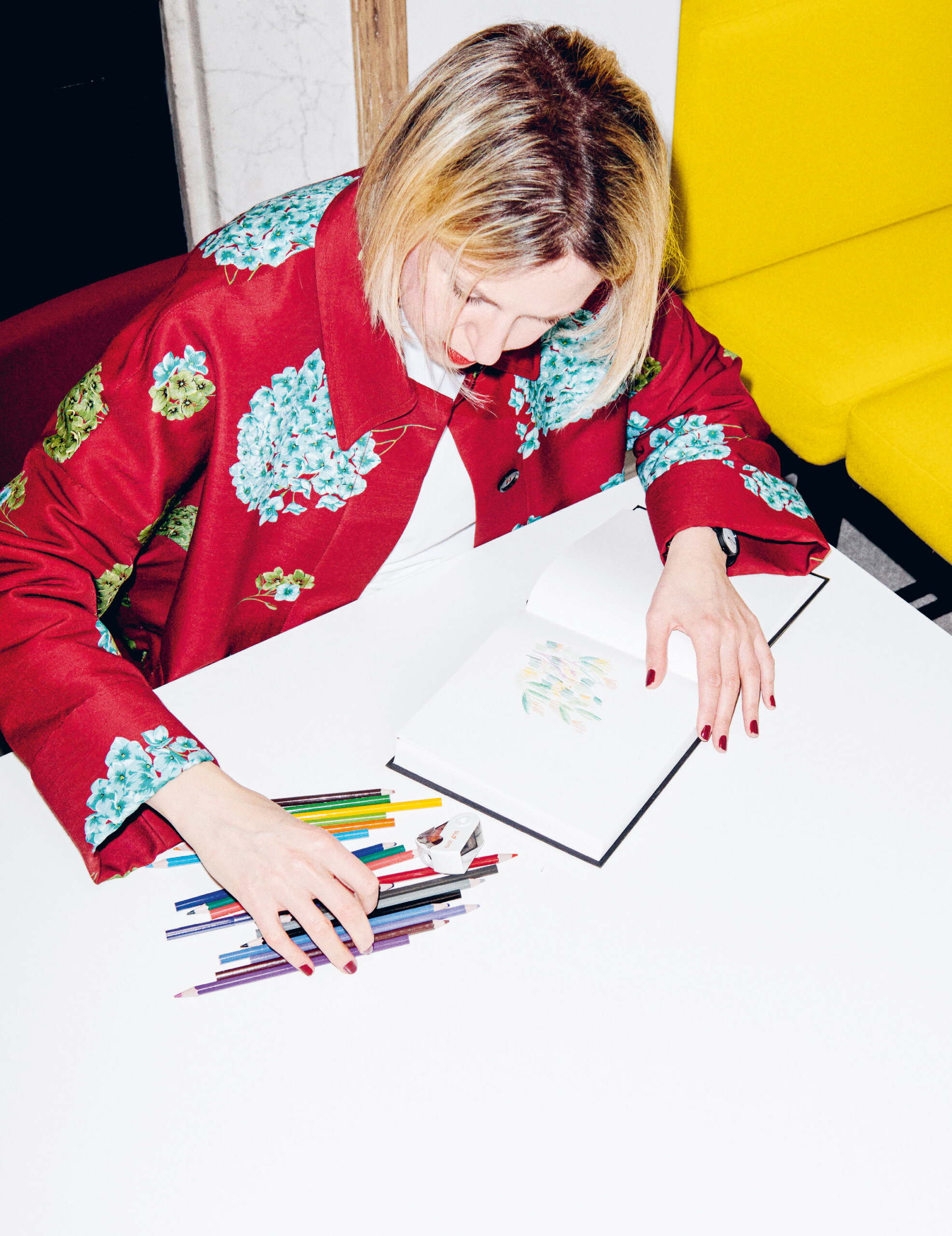

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg

It’s not easy to find time with Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg for an interview. But we manage to talk, even though she’s currently working on projects including two major undertakings–her first US solo exhibition at the Toledo Museum of Art, which she will open in April 2023, and a Pollinator Pathmaker Edition for the LAS Art Foundation at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, which she hopes to bring to bloom by summer. The Berlin flowering garden, created as a perfect work of art for insects rather than humans, is the third edition of Daisy’s Pollinator Pathmaker living artwork after she created gardens for the Eden Project in Cornwall and for the Serpentine Galleries in London in 2022 as part of their exhibition, Back to Earth.

ALEXANDRA

DAISY

GINSBERG

Right at the start of our conversation, Daisy, who holds an MA in Architecture and both an MA and a PhD in Design Interactions, clarifies, “I no longer call myself a designer. I decided to be an artist.” This comes across as so authoritative that I don’t ask further, but it becomes self-explanatory as our conversation progresses. Her artworks are as multi-layered as the technologies and associated possibilities that occupy us humans in our attempts to ‘improve’ the world. Provocative, speculative and intelligent, she always provides a new perspective on this endeavour and, ultimately, herself becomes a caretaker of other living beings.

THERE IS NO PERFECT

REPLACEMENT.

YOU CAN'T RECREATE

A ONE-TO-ONE OF

THE NATURAL WORLD

Your artwork has something ambiguous; on the one hand, you show the loss of creatures such as the last male northern white rhinoceros in The Substitute or the dawn chorus in Machine Auguries, but on the other hand, the digital technologies you use give the impression that they can provide a perfect substitute for that loss.

A

D

G

That’s exactly the question. It’s important to highlight that these are not perfect reproductions. The work gives us an impression of a perfect recreation. But when we start looking at the detail, it’s far from the real thing. That’s my point: once nature is lost, it’s lost. Nature is a very broad term because it will continue in some form. Nature is this planet, including us. But the focus of the work, and what interests me most, is really biodiversity, its loss that tortures me and fuels my own moral panic, and the lack of care that we give it. I’m playing with this ambiguous tension between nature and technology, how we seemingly pit them against each other. Why are we so focused on innovation rather than on preservation or conservation?

-

-

-

-

Is this something that will characterise our future anyway? Will aspects of nature only be experienced in the form of a digital reproduction, which is almost perfect—like the bird concert that you designed—but still only a digital replacement?

A

D

G

If we want the world to look like the world that we experience and enjoy now, then these technologies are never going to be a substitute. They’re an imperfect copy. The Substitute is not a real male rhinoceros. The 3D model doesn’t even have genitals! Its vocalisations are taken from recordings of the last eight northern white rhinos, when they were at Dvůr Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic in the early 2000s. Now there are only two females of the subspecies left. The sounds my copy makes are a mixture of eight different rhinos, male and female, and taken out of context. To us, to non-rhinos, it looks like a rhino, it sounds like a rhino. But to a rhino, it’s not a rhino. It’s the same with Machine Auguries, my reconstruction or recreation of a dawn chorus. It’s completely without context. If you played the sounds I have generated using AI back to one of the individual species, they may not recognise it. An AI-powered bird ID app can recognise the songs I’m generating. It’s been trained on recordings of existing songs, and it can identify the patterns as similar to what it has heard. But for a bird, it may just be noise, or it may even be problematic. That’s crucial to this question of ambiguity: there is no perfect replacement.

You can’t recreate a one-to-one of the natural world. Even the recordings that I’m using are not the real thing, they are recordings of those things. There’s always a human, technological filtering of the records of the natural world. I like the ambiguity, because I want the audience to come to this question on their own and evaluate their feelings towards it.

-

-

-

-

In your work, you collaborate a lot with scientists. What is their reaction to your art installations? Do they agree in some way that your artworks are relevant for generating some kind of warning or impact, or even, say, transformation?

A

D

G

I think it depends on which scientists! I love working with scientists because I can ask them questions, learn from them and be inspired by their own processes and approaches to the world. But science is not a monolith; it is made up of individuals within specialisms. I’ve spent a lot of time working with synthetic biologists, for example, and AI scientists, whose objectives and ideologies are generally different from those of conservation scientists and ecologists.

-

-

-

-

What are those different approaches, and how do they influence your work?

A

D

G

What I’ve seen is that biotechnologists’ work—at least, the way I interpret it—is very focused on human benefit. Conservation scientists are also potentially focused on human benefit, but in a broader sense of the natural world around us. Of course, these are my prejudices and generalisations! But what is most enjoyable is the conversation I have with scientists in representing my worldview, or my non-expert approach to their research, and seeing how that may spark new ideas in their own practice, but also more broadly and philosophically. For example, I’m currently making life interesting for some bird experts in the US who I’m collaborating with for a new iteration of Machine Auguries at the Toledo Museum of Art, because I need specific end-times for when the birds sing in the morning in order to construct my composition for the dawn chorus in Toledo, Ohio. I first made this work about a UK dawn. Kenn and Kimberly Kaufman were telling me, The birds don’t stop singing at a particular time, they sing all day. You’re referring to something that’s probably more endemic in the UK, where there is more noise and light pollution! Beyond downtown Toledo, it’s less of an issue. I replied, Well, this is a work of fiction. We need to bend the science to tell a truthful story about the fragility of bird populations. That’s a specific example, but it shows what’s interesting in bringing two ways of thinking together.

Working with synthetic biologists, my intention was to work critically and to ask questions about what it means to design living things, what is good design, and who gets to decide. We had fascinating conversations because I was coming from a very different perspective.

-

-

-

-

Your work relates to nature in different ways—be it that with the help of biotechnology, plants can make things grow for us, or that engineered bacteria can function as markers of diseases in our body—which could perhaps be described as a form of cooperation between humans and nature. However, your current work is increasingly concerned with the loss of nature, especially the extinction of species. Would you say there is a shift in your work approach, and how did the change come about?

A

D

G

I spent over a decade working with synthetic biologists after encountering the field in 2008. It was very much in its early stages. Synthetic biology itself was defined and established around the year 2000. But it’s really an extension of genetic engineering, albeit with a very specific ideology, which is that biology is programmable. It’s this ideology that interests me. It brought me into the worlds of engineering and biology and into thinking about the human exploitation of living things. After years of fascinating interactions, and creating work around them, I went back to the Royal College of Art to do my PhD. Through that process, I saw a bigger frame of questions that I wanted to look at next.

Now I’m making work about the environment and biodiversity to think about humans’ relationships with nature. I wanted to dedicate my practice to bringing attention to the threats facing our natural environment. There are many other more effective ways to do this. I could—and should—be an activist; I should be protesting on the street, as we all should. But in my professional life, I can devote my work to these questions and find new ways to tell stories and highlight the work that people are doing in other fields. Yesterday, I had the most moving experience doing an Instagram Live as part of our series for The Lost Rhino exhibition, which I curated at London’s Natural History Museum and which includes The Substitute. The exhibition is about the reproduction: the idea of an animal and our interest in the representation over the animal itself. Our final episode of the Lives was with an amazing young Kenyan activist conservationist, Winnie Cheche, and the Head of Conservation at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya, Samuel Mutisya. That’s where Sudan, the last male northern white rhino, lived, and where the two surviving females are.

During the Live, these two rhinos roamed around behind Samuel as we talked. I found it so emotional because I’ve never met these rhinos, I’ve never had the opportunity to see them in the flesh. And this is the closest I’ll probably ever get to them and to their essentially extinct subspecies, delivered through this strange technology, and this strange format. But really, the whole effort behind this exhibition and the storytelling is to give a platform to these two people to reach new audiences who need to hear what is happening. People joined in from all over the world as we used the Natural History Museum’s leverage to bring more awareness through a very different route to think about conservation. And that direct connection, with the animals present, was so powerful for me.

-

-

-

-

That is amazing! Have you ever considered how to measure the impact of your work?

A

D

G

In my PhD, even though it was about the idea of better, I tried to avoid the issue of measuring my own work! Museums can measure visitor numbers and there are other scientific ways to measure impact. But I just want to make work, put it out there and try to engage people. That said, the number of people who’ve been through The Lost Rhino is extraordinary, and it’s impactful if some of those few hundred thousand visitors feel some connection with the rhino in a way that’s different to experiencing the museum’s taxidermied rhino, which was killed 130 years ago, in its normal display context in the mammal hall. If they come to a different way of thinking about the animal and the collections, that’s powerful. But the real question for me is, what do they do with that?

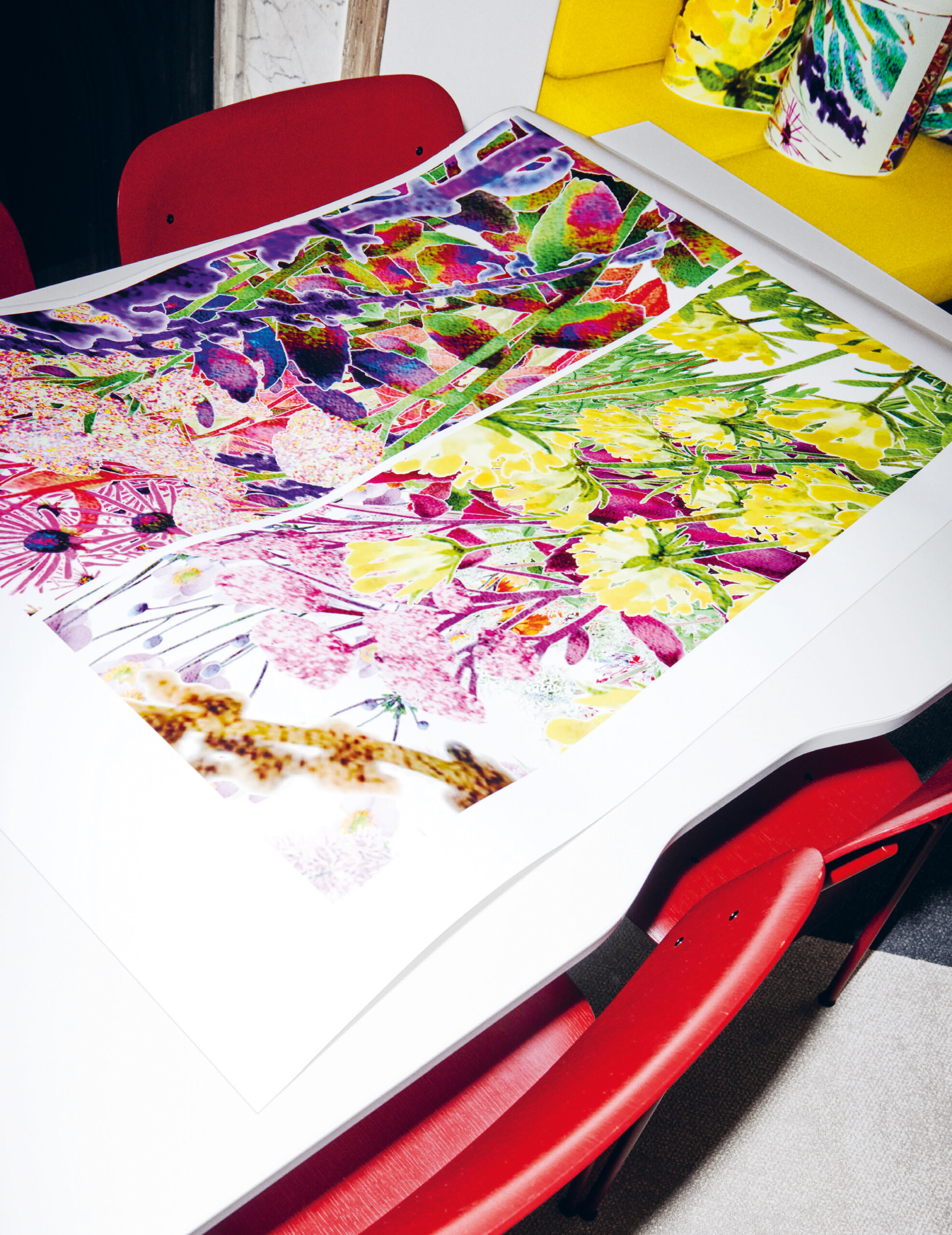

That leads to my Pollinator Pathmaker artwork and the difficulty we have in the studio of measuring its impact, which in this case I do want to measure. I want to make the world’s largest climate-positive artwork, but I don’t know how many people have planted their own DIY editions created using the website, www.pollinator.art. I can see from the analytics how many people have downloaded the planting instructions, but we haven’t had the means to track it through. It’s something that I want to figure out. And I hope we can.

-

-

-

-

You just mentioned Pollinator Pathmaker. This work is special because it’s not a tool primarily for creating a beautiful flowering meadow for us; the algorithm is focused on the needs of insects so that they can pollinate flowers in the best possible way, and it creates planting designs that maximise the diversity of pollinator species. It is a digital tool that determines the best possible planting scheme according to certain specifications. Pollinator Pathmaker shifts our perspective and builds on our empathy for these creatures; it helps us to care for them. This work is different from your previous work, in that it is less of an art installation and future speculation and more a designed and functional tool to make something better. Do you agree?

A

D

G

I agree completely!

Please select an offer and read the Complete Article Issue No 14 Subscriptions

Already Customer? Please login.